Authored by Christopher Whalen via TheInstitutionalRiskAnalyst.com,

As we head into Q4 2019 earnings this week, US financials have never been so expensive and risk indicators have never been so skewed.

Just as last July we called the problems brewing in the short-term money markets in a discussion on CNBC’s Halftime Report with Mike Mayo of Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC), today we want to put down a marker regarding the concealed credit risk inside US banks.

Our favorite bank portfolio holding, U.S. Bancorp (NYSE:USB), closed Friday at 1.87x book value, down about 5% from the peak in December just over $60 and 2x book. Still a little too rich to add more to our portfolio of USB common, but we continue to accumulate a number of bank preferred issues. With the number of profitless unicorns dying at an accelerating rate, steady cash flow has a certain appeal right about now.

More important, credit default swap (CDS) spreads for high quality issuers are also at all time lows. JPMorganChase (NYSE:JPM) is inside 40bp or around a “A” rating for the largest bank in the US. In 2015, JPM’s CDS was trading close to 120bp over sovereign swaps. Question is, does the market know, really, how much risk sits on Jamie Dimon’s books in the world of corporate CDS and more obscure credit products, like “transformation repo.” We think not.

For those not familiar with the wonders of OTC derivatives and collateral swapping, see our 2019 comment “HELOCs and Transformational REPO.” We wrote in March of last year: “The dealer bank trades corporate debt for cash (for a fee), but uses its own government or agency collateral to meet the margin call for the customer. The bank holds the crap and all of the market and credit risk – sometimes for its own book, sometimes for clients. Tales of MF Global. Recall that the margin rules in Dodd-Frank and other laws and regulations around the world are meant to increase the proverbial “skin in da game” for swaps customers, especially the non-bank customers of banks.”

Outgoing Bank of England governor Mark Carney worries that the global economy is heading towards a “liquidity trap” that would undermine central banks’ efforts to avoid a future recession, according to the Financial Times. Former Fed Chairman Benjamin “QE” Bernanke is screaming for new fiscal policy measures to combat a non-existent recession – this as the negative after effects of “quantitative” monetary policy measures are growing.

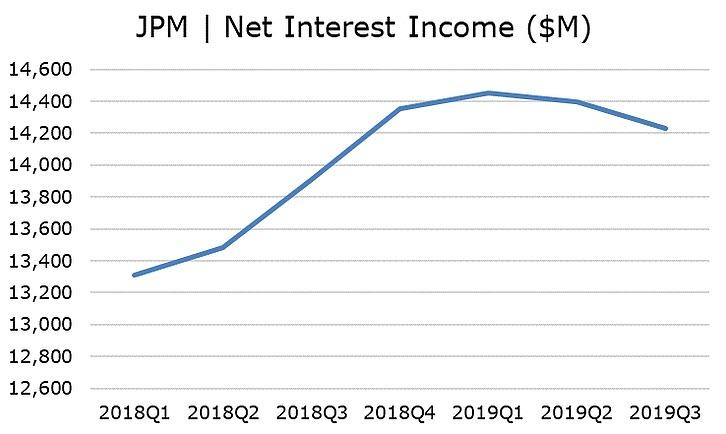

These central banksters may be right, but to us the bigger question is the unrecognized threat to the financial system from underpriced long-credit positions embedded on the balance sheets of global banks and bond funds. Bank interest earnings have long been subsidized by QE, but now banks are being squeezed by the same forces of market manipulation as credit starts to roll over. Suffice to say that the Street seems to finally understand that bank earnings are going to be a tad light, again, this quarter, due to the hangover from Uncle Ben’s QE electric KoolAid. The chart below shows net interest income for JPM.

Source: FFIEC

Despite the rosy economic outlook, bears continue to see reasons for despair in the world of credit – and we agree. The repo market sailed through year-end cushioned on a soft pillow of liquidity provided by Federal Open Market Committee. With the Fed announcing an end to the not-QE liquidity injection operations, though, we look forward to the next learning-by-doing adventure from Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell.

Should the repo markets again start to seize up when the Fed ends its extraordinary liquidity injections, then Chairman Powell’s job may actually be on the line – and not because of President Donald Trump. The looming threat to Powell and other members of the FOMC is the tightly coiled but largely invisible long credit/short put positions on the books of major banks. This is a largely hidden risk that arises from years of market manipulation by global central banks. But hold that thought…

We appreciate the flow of questions and comments about the latest IRA Bank Profile on Deutsche Bank AG (NYSE:DB). As we wrote in the profile:

“We assign a negative outlook to DB and have little expectation that the situation will change in the near term. In our view, the most promising way to resolve what is an increasingly precarious situation would be for DB to sell its US operations in their entirety and wind up the remaining bank operations. Since Germany political leaders refuse to consider such a possibility, we expect that DB will stagger along, depleting capital and creating outsized risks, until such time as the bank’s poor management makes a mistake of sufficient magnitude to cause the bank to fail.”

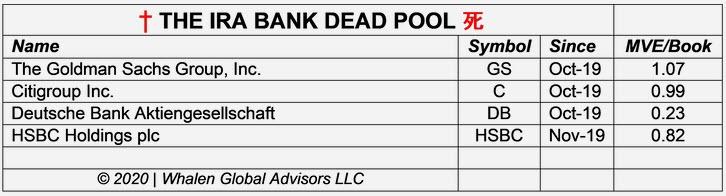

Just to review, DB is one of four value destroyers in The IRA Bank Dead Pool. Banks that are members of the IRA Dead Bank Pool have poor financial performance, inferior equity market valuations and no apparent plan to correct these deficiencies. Even with US financials at the highest equity market valuations in a decade, the four institutions in the IRA Dead Pool – DB, Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS), Citigroup (NYSE:C) and HSBC Holdings (NYSE:HSBC) – all trade at or below book value. DB has the lowest multiple of equity price to book value of any major bank.

In a recent twitter post, our pal @Stimpyz1 reminds us that negative interest rates are not the only source of risk to global banks.

“Deutsche bank might be in the crosshairs, but don’t forget HSBC,” he avers. “Hong Kong is looking like a black hole, and HSBC exposure to real estate on the island makes the DB balance sheet look like Microsoft.”

Like DB, HSBC’s US operations are in pretty bad shape, with years of credit losses and poor operational performance. Once upon a time, HSBC was a good comp for Citigroup, but today we would not even bother running the numbers. But when it comes to risk, we are far more focused on the bond market than banks, which are generally under-leveraged but contain a lot of undisclosed credit risk.

The lingering negative effect of the Bernanke-Yellen monetary benevolence is so pronounced in fixed income that a number of institutional managers we know have begun to lighten up on investment grade (IG) exposures based on the belief that a ratings-driven correction is coming. Michael Carrion of TCW wrote before the holiday:

“Much ink has been spilled this year on the topic of how strong the technicals are within the investment grade credit market and for good reason as they have been the dominant underlying driver of overall IG spreads all year. The resurgent strength derives from this year’s re-expansion of central bank balance sheets, which has resulted in a relentless supply/demand imbalance for IG bonds. Demand for IG credit reached a year-to-date peak in November, particularly in the second half of month as the pace of primary market new issuance slowed.”

Patti Domm of CNBC, quoting a research report from Hans Mikkelsen, head of investment grade corporate strategy at BofA Securities, wrote after the close on Friday: “Lured by low rates, companies issue high grade debt at one of the fastest paces ever this week,” this as interest rates touched a three-year low. The combination of market reaction to political uncertainty and central bank purchases of risk-free debt has created a credit trap for global banks and bond investors.

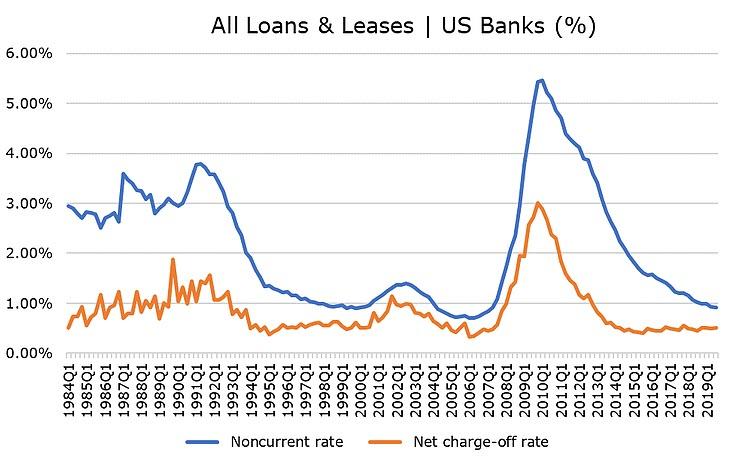

One of the things we learned from our colleague Dennis Santiago years ago at Institutional Risk Analytics is that when a credit spread looks to good to be true, it probably is. In those days, we’d convert the apparent default rate of a bank portfolio into a bond rating equivalent, then look at loss given default (LGD) to try to figure out how much the rate was understated. Today LGDs in the real estate sector are so skewed as to suggest that default rates are understated by at least 100%.

At the end of Q3 2019, the implied rating on the 0.51% of gross defaults for the $10.5 trillion in loans held by all US banks mapped to a “BBB” rating using the S&P default scale. If you believe that the aggregate rating of all obligors of US banks is investment grade, then we have some WeWork shares we’d like to sell you. Step right up.

Source: FDIC

The issuance of IG debt has set new records for the past several years, but most of this paper is clustered around “BBB” ratings. This suggests that the proverbial lemmings could fall off of the ratings cliff with little or no notice. As we all hopefully learned in the Adam McKay film “Big Short,” the major credit rating agencies don’t have the capacity or the courage to react quickly as and when economic and/or market conditions dictate a change for dozens of issuers. The investors that own long positions in underpriced corporate risk positions will be long dead before the ratings change.

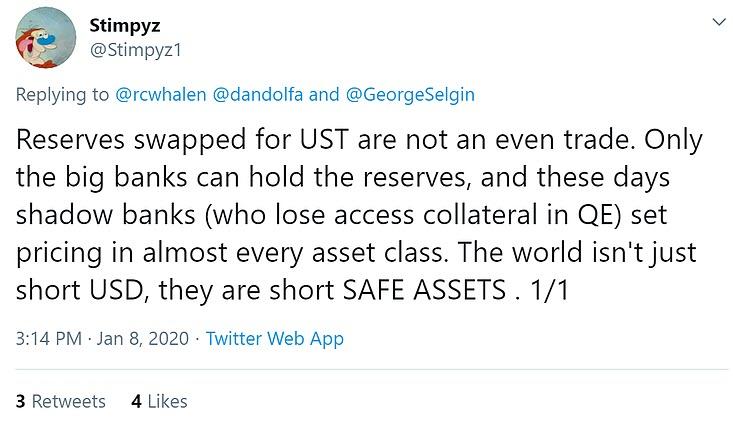

The potential ratings volatility embedded in corporate debt has huge implications for banks, which have been “transforming” crap collateral into high IG in order to partially satiate the investor demand for low- or no-risk paper. TCW confirms our earlier colloquy with @Stimpyz1 on Twitter the other day:

This implies that there is an embedded credit put on the books of a lot of banks and funds as and when the QE party well and truly ends. Perhaps this is why John Carney and Ben Bernanke are so insistent of a shift to fiscal stimulus. But it needs to be said that no amount of fiscal push will fix the credit risk that the Fed and other central banks have created via “quantitative easing.”

We’ve been talking about the misalignment of credit ratings and corporate fundamentals for the past several years, but the continuation of QE in Europe and Asia has managed to prevent a reversion to the valuation mean. The divergence seen in junk rated collateral sold into collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and superior credits suggests to us that an adjustment may finally be underway. The inferior assets always fall first. And to recall John Kenneth Galbraith’s great book about the 1920s: “Genius comes after the fall.”

While interest rate movements are suppressing net interest margins at major US banks, the prospect of a wholesale slip below investment grade for literally hundreds of weak bond issuers may be a far more worrisome problem. Bad ratings concealed the true risk in billions of dollars-worth of mortgage backed securities prior to the 2008 crisis. The new area for securities fraud and ratings malfeasance is the corporate bond market. If you think the liquidity problems we saw last summer in plain vanilla repo were bad, imagine what happens when margin calls on collateral swaps start to swamp the dealer banks.