Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

$21 billion of debt. Off-balance-sheet entities. Moody’s wakes up, downgrades it four notches, with more to come.

Steinhoff International Holdings – which acquired nine companies in the past two years, including Mattress Firm Holding in the US, and which presides over a cobbled-together empire of retailers and assorted other companies in the US, Europe, Africa, and Australasia – issued another devastating announcement today: It cancelled its “private” annual meeting with bankers in London on Monday and rescheduled it for December 19.

This is the meeting when the company normally discusses its annual report with its global bankers. The annual report should have been released on Wednesday, December 6. But on precisely that day, the company announced cryptically that “accounting irregularities” had “come to light” that required “further investigation,” and that CEO Markus Jooste had been axed “with immediate effect,” and that it would postpone its annual report indefinitely.

This is raising serious questions about the company’s viability as a going concern. The lack of transparency doesn’t help.

To soothe investors, the company announced on Thursday that it was trying to prop up its liquidity by selling some units ASAP. And it made more cryptic statements: It “has given further consideration to the issues subject to the investigation and to the validity and recoverability” of some assets of “circa €6 billion” ($7 billion).

“The validity and recoverability” of assets worth $7 billion? The company is infamous for its opaque communications which equal its opaque corporate structure.

It’s considering selling “certain non-core assets that will release a minimum of €1 billion of liquidity.” It also “committed” to wringing out €2 billion from its subsidiary Steinhoff Africa Retail Limited (STAR) by refinancing “on better terms” some debt that the subsidiary owes the parent company, which the subsidiary should be able to handle, “given the strong cash flow.”

With these measures, it hopes “to be able to fund its existing operations and reduce debt.” Shareholders and bondholders were aghast.

The shares, traded in Frankfurt and held widely by international investors, had still been in the €5-range in June. But in August, German prosecutors said they were probing if Steinhoff had booked inflated revenues at its subsidiaries. Shares began to drop. By Tuesday, there were down 41% at €2.95.

On Wednesday, after the “accounting irregularities” had “come to light,” shares crashed 64% to €1.07. By Friday, they’d dropped to €0.47. Market capitalization plunged by about €18 billion ($21 billion) since June to €2 billion.

On Thursday, given the fiasco, Moody’s downgraded the company four notches in one fell swoop, from Baa3 (one notch above junk) to B1, which is well into junk, and added “on review for further downgrade.” It said:

Given that allegations of accounting irregularities were raised and rebutted in August 2017 and again in November 2017 it calls into question the quality of oversight and governance at Steinhoff.

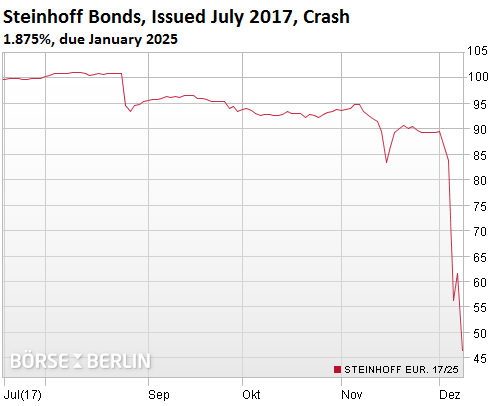

The €800 million of bonds that Steinhoff Europe AG issued during the halcyon days of June 2017 had traded at over 100 cents on the euro in August. By Tuesday, they’d dropped below 85. On Wednesday they crashed to 56. On Friday, they closed at 46.56 cents on the euro:

Moody’s 4-notch downgrade with more downgrades likely shows once again how credit ratings are lagging indicators that merely give investors confirmation of what the plunge in price has already shown in gruesome detail.

But Steinhoff owes its banks a lot more than its bondholders – the same banks with which it was supposed to meet on Monday. According to Bloomberg, the company’s “total exposure to lenders and other creditors was almost €18 billion ($21 billion) as of the end of March.”

“The great unknown is the funding of the off-balance-sheet structures, which could spill over into fresh bank liability,” Adrian Saville, CEO of Cannon Asset Managers in Johannesburg, told Bloomberg. He said the short-term debt could “fall over if the business fails.”

These are the banks, according to Bloomberg, that are exposed to the company, its off-balance sheet vehicles, and the investment vehicles of its Chairman Christo Wiese, globally:

- Citigroup

- Bank of America

- HSBC

- BNP Paribas

- Goldman Sachs

- Nomura Holdings

And in South Africa:

- Standard Bank Group

- Investec

- Rand Merchant Bank, a unit of FirstRand

Bloomberg explains:

Last year, [Wiese] the billionaire and largest shareholder of the company pledged 628 million of Steinhoff’s shares in collateral to borrow money from Citigroup, HSBC, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Nomura Holdings Inc. That was to participate in a share sale in conjunction with the acquisition of Mattress Firm and Poundland, according to a company statement.

The value of those pledge shares has plunged to €301 million, from about €3 billion a year ago.

“The disclosures have also turned a fresh spotlight on a set of transactions involving related entities that critics say may have hid operational losses and artificially pumped up the company’s valuation,” according to The Wall Street Journal.

The German prosecutors said in August that, according to the Journal, “they suspect the revenue came from a set of contracts, each valued in the hundreds of millions of dollars, that Steinhoff subsidiaries sold to undisclosed related parties.”

This week, analysts scrambled to make sense of some of the transactions, parts of which are publicly disclosed. In the past, some transactions had triggered specific concern by analysts. Despite those questions and the German probe, investors had largely been satisfied with Steinhoff’s public explanations – until now.

“It’s the unknown unknowns that are the big worry here. You’ve got to ask, ‘Who knows the whole story?’” Brian Pyle, an analyst at Old Mutual Investment Group, told the Journal. The firm is one of Steinhoff’s top-20 shareholders. “We just don’t know what else is out there.”

In one widely circulated research report published anonymously Tuesday, a group calling itself Viceroy Research accused Steinhoff of using companies owned by some of its former executives and other close associates to hive off unprofitable assets. Those disposals, Viceroy alleges, were often financed by loans from Steinhoff, the interest from which Steinhoff booked as revenue.

Viceroy said some of these transactions involved Campion Capital SA, a Swiss private-equity firm. Campion directors include Siegmar Schmidt, a former finance chief at one of Steinhoff’s subsidiaries, according to public records and other documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

In 2015, Steinhoff Möbel, a Steinhoff subsidiary, entered into a joint venture with a company owned by Campion, according to these records. The joint venture then bought a company called GT Global Trademarks from Steinhoff.

The following year, Campion bought two consumer-loan units from South Africa-based Steinhoff Africa Holdings, a Steinhoff International subsidiary. It then sold parts of those firms seven months later to Pepkor, a South African retailer owned by Steinhoff’s Johannesburg-listed subsidiary, according to a determination by the South African Competition Commission in October of that year.

The terms of both transactions are unclear.

And there were more indications. The Journal:

In Steinhoff’s third-quarter earnings call in August, a credit analyst from HSBC asked then-Chief Executive Markus Jooste why the company was taking on debt and entering into complex partnerships even though its balance sheet showed it had plenty of cash.

Mr. Jooste answered that the joint ventures “had nothing to do with liquidity or monetary terms” and that it just wanted to have local partners who understood how to grow its business.

Reuters reported in November that Steinhoff “did not tell investors about almost $1 billion in transactions with a related company despite laws that some experts believe require it to do so.” Short-seller Viceroy Capital, mentioned above, has alleged that Steinhoff used such related-party transactions to channel losses off its financial statements.

Steinhoff’s roll-up strategy made it practically impossible for investors – even those tempted to try – to establish underlying cash flows, revenue growth, and earnings. But these schemes cannot be carried on forever.