Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Exchange-traded bond funds and bond mutual funds are big business. They’re a lot easier for retail investors to buy and sell than the actual bonds, particularly bond ETFs, which trade on stock markets just like stocks — and can even be day-traded. But this liquidity for investors is precisely the potentially catastrophic problem.

And in this era of rising interest rates and deteriorating credit, bonds already have plenty of other problems.

Corporate America carries record amounts of debt. Part of this debt is in form of bonds (the other part is in form of loans). The amount of bonds outstanding has ballooned over the past five years, even as the credit quality has deteriorated. Now there are $6.1 trillion of investment-grade US-corporate bonds outstanding, according to Moody’s (plus over $1.2 trillion of “junk bonds”). These bonds are everywhere, including in bond ETFs and bond mutual funds, and therefore in retail investors’ portfolios.

So as an example, let’s look at the largest, most diversified investment-grade bond ETF, the iShares iBoxx [LQD], with $30.5 billion in assets. It currently has a trailing 12-month yield of 3.25% and a “30-day SEC yield” (explanation) of 4.4%. Tempting, right?

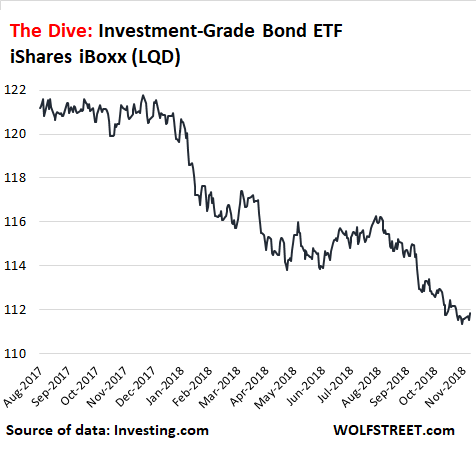

But the ETF’s price on Wednesday dropped to $111.30 intraday, down 7.5% year-to-date and down 8.4% from a year ago – and the lowest price since 2011. Then the price ticked up to close at $111.85 as the stock market, where this ETF is traded, eagerly interpreted Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s speech as seemingly “dovish,” though the 10-year Treasury yield, after some gyrations closed unchanged. Still, the ETF is on track for its worst year ever. And this is the good stuff – not some Emerging Market bond fund:

Investment-grade corporate bonds are all those rated from BBB- to AAA. Speculative or “junk-rated” bonds are rated BB+ and below, down to D for “default” (here is my cheat sheet for the bond rating scales used by Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch).

The iShares iBoxx ETF holds investment-grade corporate bonds. These are the top 10 holdings (% issuer weight within the fund):

- JPMorgan Chase (3.0%)

- Bank of America (2.9%)

- Goldman Sachs (2.7%)

- Verizon (2.5%)

- AT&T (2.4%)

- Citigroup (2.4%)

- Morgan Stanley (2.2%)

- Comcast (2.1%)

- Apple (2.1%)

- Microsoft (2.0%)

Banks dominate the fund, accounting for 27.5% of the bonds in this ETF. So let’s hope that banks don’t start wobbling again. But that’s not the Big Worry.

The Big Worry with bond ETFs and open-end bond mutual funds is the “liquidity mismatch,” which, if a “run on the fund” occurs, can lead to a catastrophic loss for investors.

When the market gets stressed, a large number of investors can sell these bond ETFs at the spur of the moment to get their money out. When enough investors sell their bond fund, that fund would be forced to sell some of the bonds it holds. Even during relatively liquid moments, corporate bonds cannot be sold quickly. And during times of stress, liquidity can dry up, and the only buyers left may be some hedge funds bidding cents on the dollar.

This might be OK for a while, as the ETF can unload the most liquid bonds first, such as Treasury securities it holds for that purpose along with some of the more liquid corporate bonds. And during a normal bond sell-off, that’s good enough.

But if markets get rougher, and as bond prices decline more sharply, investors get nervous and start getting out of bond funds in general. And getting out of a bond ETF is the easiest because it can be sold like stocks. And these bond ETFs (along with open-end bond mutual funds that experience a run) are then forced to sell corporate bonds into a market with little liquidity and falling prices. As a result, the price of these bond ETFs will fall by a lot.

Investors who own the bonds outright collect their coupon payments and, if the company doesn’t default, will get their money back when the bond matures. These investors can sit out the panic.

But bond ETF holders and bond mutual-fund holders may get crushed. The fund is forced to sell those bonds at the worst possible time to hedge funds and private equity firms just waiting for this moment, for cents on the dollar. Then, when the market recovers, the ETF cannot participate in the recovery of the bonds it was forced to sell, and there won’t be much of a recovery for ETF holders. The loss will be permanent.

And just the fear of this event happening can cause a “run on the fund,” when investors try to use the “first-mover advantage” (FMA) and bail out. It can cause a bond fund to collapse.

This is the worst-case scenario for bond-fund investors. The likelihood that it occurs is small – until it isn’t. A number of bond funds collapsed during the Financial Crisis, such as Charles Schwab’s $13-billion bond fund SWYSX. And at least one bond fund collapsed during the Oil Bust in December 2015. When this type of collapse occurs, however small the chance, it’s catastrophic for investors.

It’s the risk of losing a large part or most of your principal, despite the high-grade bonds in the fund, most of which will get through the rough spot just fine. Fund investors are never paid to take this risk.

Then there is another problem with a much higher likelihood of occurring – in fact, it’s nearly guaranteed to occur over the next year or two, though the consequences are not nearly as catastrophic as a run on the fund. It affects all bondholders, directly and indirectly. And in the end, it could contribute to triggering a run on one or the other fund.

Top-rated bonds, such as Apple’s or Microsoft’s, will weather the fallout without problems. But “investment-grade” includes a lot of bonds that are barely above junk – namely bonds rated BBB (between BBB+ and BBB-). According to Moody’s, this is how the investment-grade US corporate bonds are divvied up:

- AAA & AA-rated: $0.63 trillion

- A-rated: $2.62 trillion

- BBB-rated: $2.83 trillion

In other words, of all these $6.1 trillion of investment-grade bonds, 46% are BBB-rated, awaiting their down-grade to junk — to become “fallen angels.” John Lonski, Chief Economist at Moody’s Capital Markets Research:

Thus, from the perspective of dollar amounts outstanding, the U.S. investment-grade corporate bond market is now riskier than it was prior to each recession since 1981 and possibly all prior downturns through the late 1940s.

As financial conditions tighten and interest rates rise, refinancing maturing debt gets more difficult and more expensive for junk-rated companies. Those that cannot roll over their maturing debt will default. A slowdown in the economy causes further deterioration of their cash flows — they’re junk-rated because they already have too much debt for the amount of cash they generate — which will cause a slew of them to be unable to even make interest payments; and they too will default on their bonds. And many of the $2.8 trillion of BBB-rated bonds, now safely tucked away in investment-grade bond funds, are facing that fate.

So, there is a lot to think about when investing in these super-convenient and conservative-sounding bond funds during these times of rising interest rates, with a down-turn lurking somewhere in the future, as the credit cycle has already turned south, and as losses are already piling up, though these are still the good times.

A big shift at GM, at a cost of $3.8 billion. Read... After Wasting $14 billion on Share-Buybacks, GM Prepares for Carmageddon & Shift to EVs, Cuts Employees, Closes 8 Plants