Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

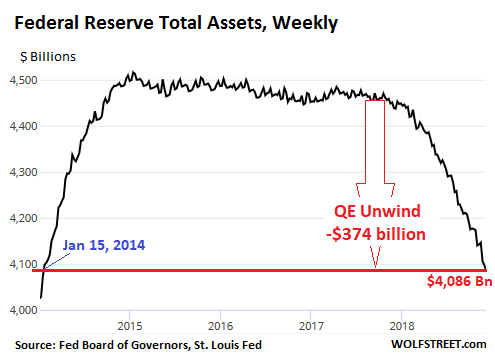

The Federal Reserve shed $54 billion in assets over the five weekly balance sheet periods that encompass the calendar month of November. This reduced the assets on its balance sheet to $4,086 billion, the lowest since January 15, 2014, according to the Fed’s balance sheet for the week ended December 5, released this afternoon. Since the beginning of the QE unwind — or “balance sheet normalization,” as the Fed calls it — in October 2017, the Fed has now shed $374 billion:

The Fed holds a variety of assets, including the Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) that it had acquired as part of QE. Between the end of QE in late 2014 and the beginning of the QE unwind in October 2017, the Fed replaced maturing securities with new securities to keep their levels roughly the same. Starting in October 2017, the Fed has been shedding Treasury securities and MBS.

How much lower will the balance sheet go?

The Fed held about $910 billion in assets in the summer of 2008, before the whole mess started. Over the prior decades, the amount of assets on its balance sheet had roughly grown in line with nominal GDP (not inflation adjusted); and this trend would have continued. In other words, there is zero chance the assets on the balance sheet will ever revert to $910 billion.

Since Q4 2008, nominal GDP has grown by 42%. Assuming that QE continues for five more years: At the average growth rate of the past few years, nominal GDP in 2023 will have grown by 72% since Q4 2008. If the Financial Crisis had never happened and if therefore the Fed had continued expanding its balance sheet in line with nominal GDP, the balance sheet would have reached about $1,570 billion by 2023.

This marks the absolute lowest point for the assets on the Fed’s balance sheet by the time the QE unwind is finished – but more likely, the balance sheet won’t drop quite that far.

Treasury Securities

Until October, the QE unwind had been in ramp-up mode. In October, it reached cruising speed, according to the Fed’s plan. In the cruising-speed phase, the Fed is scheduled to shed “up to” $30 billion in Treasuries and “up to” $20 billion in MBS a month, for a total of “up to” $50 billion a month. So how did it go in November?

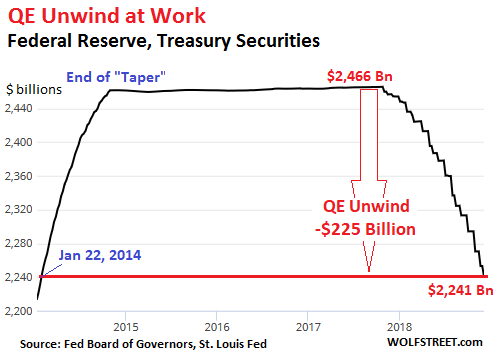

From November 1 through December 5, the Fed’s holdings of Treasury Securities fell by $30 billion to $2,241 billion, the lowest since January 22, 2014. Since the beginning of the QE-Unwind, the Fed has shed $225 billion in Treasuries:

The Fed sheds Treasury securities by allowing them to “roll off” when they mature. When Treasury securities mature, the Treasury Department sends money to all holders of those maturing bonds to redeem them at face value. Treasuries mature mid-month or at the end of the month. Hence the step-pattern of the QE unwind in the chart above.

On November 15, three issues matured totaling $34 billion. On November 30, three more issues matured totaling $25 billion. So for the month in total, $59 billion in Treasury securities matured. This was an unusually large amount, the most since the QE unwind began.

Sticking to the plan, the Fed did two things:

- It collected $30 billion from the Treasury Department for part of the securities that matured. The Fed creates money, and it destroys money; but it doesn’t sit on trillions of dollars in cash. So when it received the $30 billion from the Treasury Department, it then destroyed this money just as it had created this money to purchase these securities. That was the QE unwind part.

- The Fed also reinvested (“rolled over”) directly with the Treasury Department the proceeds of the remaining $29 billion in Treasuries that had matured.

There won’t be many months with this many Treasury securities maturing, and it will become rarer that the Fed, if it sticks to its plan, can shed the full “up to” amount capped at $30 billion a month. For example, in December, only $18 billion in Treasuries will mature, which will be the maximum that the Fed can shed under its plan.

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

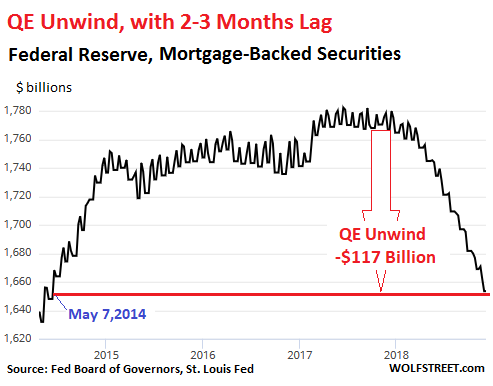

Under QE, the Fed also acquired residential MBS that were issued and guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. Holders of residential MBS receive principal payments as the underlying mortgages are paid down or are paid off. At maturity, the remaining principal is paid off. To keep the balance of MBS from declining after QE ended, the New York Fed’s Open Market Operations kept buying MBS in the market.

The Fed books the trades at settlement, which lags the trade by two to three months. Due to this lag, the amount of MBS on today’s balance sheet reflects trades in August and September when the cap for shedding MBS was $16 billion a month.

And this is how it panned out. From November 1 through today’s balance sheet, the balance of MBS fell by $16 billion, to $1,653 billion, the lowest since May 7, 2014. Since the beginning of the QE unwind, the Fed has whittled down its holdings of MBS by $117 billion:

So in November, the Fed shed $30 billion in Treasury securities and $16 billion in MBS, for a total QE unwind of $46 billion, the largest monthly amount since the QE unwind began.