Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Getting rid of MBS faster and shifting to short-term Treasury bills will be on the list.

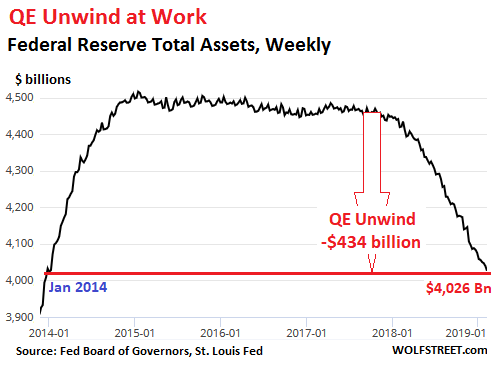

The Fed shed $32 billion in assets in January, according to the Fed’s balance sheet for the week ended February 6, released this afternoon. This reduced the assets on its balance sheet to $4,026 billion, the lowest since January 2014. Since the beginning of this “balance sheet normalization,” the Fed has now shed $434 billion.

According to the Fed’s plan released when the QE unwind was introduced in 2017, the Fed is scheduled to shed “up to” $30 billion in Treasuries and “up to” $20 billion in MBS a month for a total of “up to” $50 billion a month. So how did it go in January?

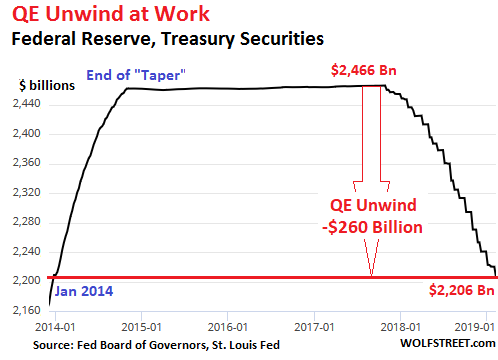

Treasury Securities

The Fed sheds Treasury securities by allowing them to “roll off” without replacement when they mature. It does not sell them outright. When Treasury securities mature, the Treasury Department transfers money in the amount of face value plus any outstanding interest to all holders of those securities. Treasuries mature mid-month or at the end of the month.

On January 15, $1.78 billion of TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities) matured, plus $305 million in inflation compensation. On January 31, three issues of Treasury notes and bonds matured, totaling $11.7 billion. This did not reach the cap of $30 billion. So for the month, all Treasury securities that matured were allowed to roll off without replacement. This, in addition to some other items, reduced the total balance of Treasury securities by $17 billion, to $2,206 billion – down by $260 billion since the QE unwind began:

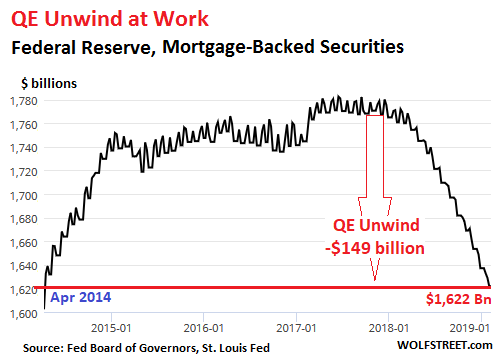

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

As part of its QE, the Fed acquired residential MBS that were issued and guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. Holders of MBS receive pass-through principal payments as the underlying mortgages are paid down or are paid off. The remaining principal is paid off at maturity.

These pass-through principal payments cause the principal amount of a portfolio of MBS to decline on an ongoing basis. To keep the balance of MBS from declining after QE had ended, the New York Fed’s Open Market Operations continued purchasing MBS in the market.

When interest rates fall, and mortgages get refinanced in large quantities, and in a period when home sales volume is high, and a lot of mortgages get paid off during the sales process, MBS principal can shrink rapidly.

But a rising interest-rate environment produces sharply lower refis; fewer mortgages get paid off to be refinanced. And when home sales volume falls, as is the case right now, even fewer mortgages get paid off. Under these circumstances, the pass-through principal payments to MBS holders slow to a trickle.

The Fed books MBS trades at settlement, which lags the trade by two to three months. Due to this lag, the amount of MBS on the current balance sheet reflects trades from late last year. In October, the cap for the MBS roll-off rose to $20 billion. But pass-through principal payments and the amount of maturing MBS does not reach that $20-billion cap every month.

In January, the balance of MBS fell by $15 billion to $1.622 billion, back where it had been in April, 2014. Since the beginning of the QE unwind, the Fed has shed $149 billion in MBS:

So the January roll-off continued to proceed on “autopilot,” as outlined in the Fed’s 2017 plan. It’s happening at a glacial pace, with a reduction of $17 billion in Treasury securities and $15 billion in MBS, for a total of $32 billion. And yet, after ignoring the QE unwind for a year, the clamoring on Wall Street and at the White House to stop this cruel and unusual punishment became deafening late last year when stocks cratered.

And hoopla erupted on Wall Street this year when the Fed said that it would be “patient” with interest rate hikes in the first half of 2019, and that it was open to tweaking the balance-sheet normalization process. The big theme was to get rid of MBS faster and replace some of them with short-term Treasury bills to bring down the average maturity of the Fed’s portfolio and give it more flexibility.

This, our Wall Street pundits interpreted to mean that the Fed had made a “U-Turn” and would soon cut rates and restart QE at any moment, or whatever.

So the questions going forward are these:

One, will the Fed continue to trim its balance sheet on “autopilot,” or will it deviate from plan and slow or stop the balance sheet reductions;

Or two, will the Fed reverse course and restart QE all over again at any moment now, as the biggest Wall Street hype-mongers have prophesied;

Or three, will the Fed tweak the roll-off – as a slew of Fed governors have suggested – to where it would get rid of its MBS more quickly by outright selling them; and by replacing some of them with short-term Treasury bills to lower the balance sheet’s average maturity, which currently is over eight years.

Over the next few months, the Fed will likely announce some tantalizing tidbits about how it might tweak the balance-sheet reduction. One of those tidbits will likely relate to how it will shed MBS faster and replace those additional reductions of MBS with short-term Treasury bills. The effects of this may not be what the markets had hoped for in their wildest dreams. And the Fed will likely dole out more clues about how much further it wants to cut its balance sheet. But all this will take months, and until those tweaks are nailed down and announced, the balance sheet normalization will proceed on autopilot at its by now customary glacial pace.

“Patient” has become the Fed’s favorite word in recent weeks. But reporters who tried to get Fed Chairman Jerome Powell to nail down what “patient” actually means, walked out empty-handed. Read... Fed’s QE Unwind to Continue on Autopilot, Rate Hikes on Hold for “Common-Sense Risk Management”: Powell