Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Then there’s the sinkhole of $1.5 trillion in MBS and $617 billion in Treasuries that mature in over 10 years.

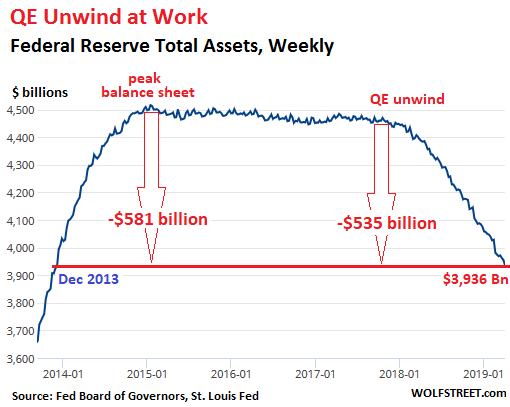

In March, the Fed shed $34 billion in assets, according to the Fed’s balance sheet for the week ended April 3, released this afternoon. This reduced the assets on its balance sheet to $3,936 billion, the lowest since December 2013. Since the beginning of the “balance sheet normalization” process, the Fed has shed $535 billion. Since peak-balance sheet in January 2015, it has shed $581 billion:

Last month, the Fed outlined its new plan for its balance sheet. The autopilot of the balance sheet runoff will be tweaked starting in May. A totally new regime will start in October. There are all kinds of changes in this new plan, primarily, that the runoff of Treasury securities will stop at the end of the September, and that the Fed wants to entirely get rid of its mortgage-backed securities (MBS), including by selling them outright, to replace them with shorter-dated Treasury securities. This strategy will finally begin to address a massive maturity-sinkhole that the Fed has carved out for itself and slipped into ever deeper. More on that in a moment.

According to the Fed’s old plan, which is still in effect, the QE-unwind autopilot is set on shedding “up to” $30 billion in Treasuries and “up to” $20 billion in MBS a month for a total of “up to” $50 billion a month, depending on the amounts of bonds that mature that month.

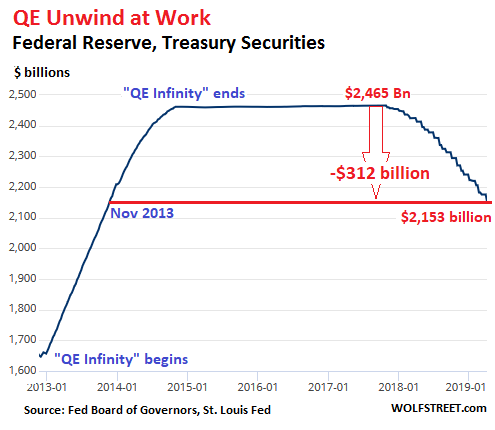

Treasury Securities

The Fed doesn’t sell its Treasury securities outright but allows them to “roll off” without replacement when they mature. Treasuries mature at mid-month or at the end of the month.

On March 15, no Treasuries in the Fed’s portfolio matured. On March 31, three issues of Treasuries matured, totaling $22 billion. This was below the $30 billion “cap,” and the Fed allowed all $22 billion to roll off without replacement. This brought its Treasury holdings down to $2,153 billion, the lowest since November 2013:

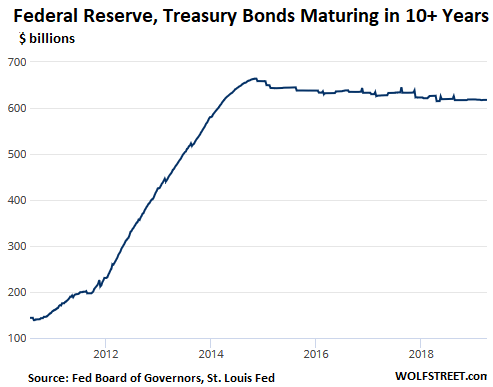

Of those $2,153 billion in Treasury securities, $617 billion are bonds maturing in over 10 years! This amount has not moved at all since August last year, though over the same time period, the balance of total Treasury securities has dropped by $183 billion. In other words, the average maturity has risen further. And as we will see in a moment, this is a much bigger issue with MBS.

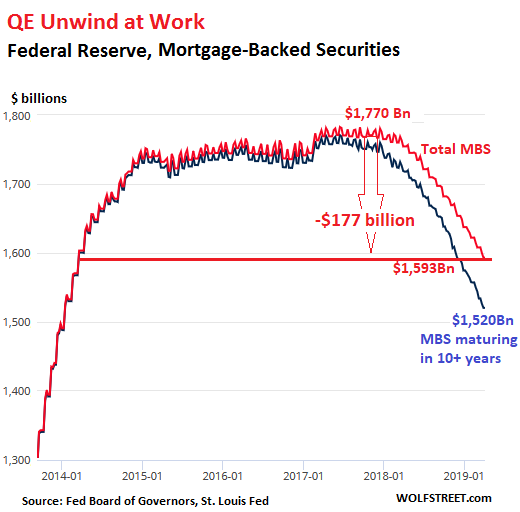

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

As part of QE, the Fed also acquired residential MBS that were issued and guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. All holders of MBS receive pass-through principal payments as the underlying mortgages are paid down or are paid off, such as when mortgages are refinanced. The remaining principal is paid off at maturity.

These pass-through principal payments cause the balance of MBS in the Fed’s portfolio to decline in an unpredictable manner. To keep the balance steady after QE had ended, the New York Fed’s Open Market Operations continued purchasing MBS in the market.

In March, the balance of MBS fell by $15 billion to $1,593 billion, the lowest since March 2014. Since the beginning of the QE unwind, the Fed has shed $177 billion in MBS.

But of these $1,593 billion in MBS on the Fed’s balance sheet, $1,520 billion mature in over 10 years!

The chart below shows the total MBS balance (red line) and the balance of MBS maturing in over 10 years (blue line), which has been shrinking slowly in part because of the pass-through principal payments:

Under the new plan, the Fed will continue shedding MBS at the current maximum of $20 billion a month until they’re gone. But that might take a long time, given their long maturities and the slow pass-through principal payments. So the Fed said in its plan that it may sell MBS outright to speed up the process of getting rid of them.

After September, it will reinvest the principal payments from the MBS into Treasury securities, likely with much shorter maturities, such as Treasury bills, of which it has none currently. This should have the opposite effect on yields that its current procedure has, with some upward pressure on long-term yields and mortgage rates, and some downward pressure on short-term yields. This would steepen the yield curve a tad.

The Fed has not yet decided on what the maturity composition of its portfolio should be or how it will get there. This decision is yet to come, it said.

And there is another twist in its new plan: In relationship to GDP, the Fed’s balance sheet will continue to shrink until some magic unknown point is reached. Read… Fed’s New Balance Sheet Plan: Get Rid of MBS