Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Their “Everything Bubble” is being pricked “gradually,” and they don’t like it.

Wall Street has been moaning, groaning, and crying out loud about the Fed’s current monetary policies – raising rates and unwinding QE. They fear that these policies will undo the Fed’s handiwork since the onset of QE and zero-interest-rate policy in 2008, now called the “Everything Bubble” (stocks, bonds, “leveraged loans,” housing, commercial real estate, classic cars, art…). In an effort to pressure the Fed to back off, they’re accusing the Fed of making a “policy mistake” and creating “scarcity” of bank reserves.

Here is Bloomberg News this morning. It’s really cute how this works. This is how the article starts out: “Fixed-income traders are telling the Federal Reserve that it might end up making a big policy mistake.”

These folks cannot say that the Fed’s QE unwind and higher rates might unwind some of the wealth of asset holders that resulted from the Fed’s desired “wealth effect.” That would be too clear. So they have to come up with hoary theories to back their “policy mistake” theme. This time it’s the theory of a “scarcity of bank reserves.”

When these folks talk about “scarcity,” what they mean is that they have to pay a little more. In this case, banks are having to pay more interest to attract deposits.

For the crybabies on Wall Street, that’s “scarcity.” For savers, money-market investors, and short-term Treasury investors, however, it means the era of brutal interest rate repression has ended, and that they’re earning once again more than inflation on their money (savers might have to shop around).

But that the money from depositors is suddenly not free anymore is anathema on Wall Street. So here we go – this time specifically targeting the QE unwind. Bloomberg:

The most vocal critics contend that if the Fed doesn’t slow or stop its unwind, it could end up draining too much money from the banking system, cause market volatility to surge and undermine its ability to control its rate-setting policy.

“The Fed is in denial,” said Priya Misra, the head of global interest-rate strategy at TD Securities. “If the Fed continues to let its balance-sheet runoff continue, then reserves will begin to become scarce.”

I receive these doom-and-gloom pronouncements about a “policy mistake” and “scarcity” of reserves all the time in my inbox, sent by economists working for Wall Street firms. They want me to cover this stuff, just like Bloomberg is covering it. It’s a ludicrous charade. But they’re out there trying to pressure the Fed with a publicity campaign to back off because Wall Street is at risk of giving up some of what it gained during the era of interest-rate repression and QE.

The Fed’s QE unwind got started in October last year and finally reached cruising speed. “Gradual” is the operative term. The Fed has shed $195 billion in Treasury securities, which are now down to $2.27 trillion; and it has shed $102 billion in mortgage-backed securities, which are now down to $1.67 trillion. Total assets on its balance sheet have dropped by $321 billion over those 13 months, to $4.14 trillion.

And every step along the way, the crybabies on Wall Street were out there whining about it.

These are the same folks who said during QE that the Fed could never stop QE, and they baptized QE-3 “QE Infinity.” And when QE Infinity ended, they said that the Fed had “painted itself into a corner” and could never shed any of these assets. And when the Fed started shedding these assets late last year, they said that the Fed would back off, and when the Fed accelerated as planned the QE unwind to cruising speed, they called it a “policy mistake” that is creating “scarcity” of whatever.

These economists are a transparent PR and lobbying joke.

Bloomberg lays out their theories that the effects of the QE unwind are “creating the scarcity of reserves that has banks – mainly the smaller ones at this point – scrambling for short-term dollar funding.”

So what are these “reserves?” These are the “excess reserves” – cash obtained from bank deposits that banks in turn place on deposit at the Fed to earn the easy and risk-free “Interest on Excess Reserves” (IOER), currently 2.20%, that the Fed currently pays. This is a great deal for banks: They pay customers next to nothing for their money and then deposit the excess cash at the Fed for an easy 2.2% return.

Or at least it was a great deal. But now banks have to raise interest rates to retain deposits, and to rope in new customers, they’re offering higher rates on “brokered CDs.” They’re having to pay 2.5% and even 3% for a one-year CD to do so. And giving up 2.2% income from excess reserves and bringing that cash back to the bank to lend out, is cheaper than having to pay customers 2.5% or 3%.

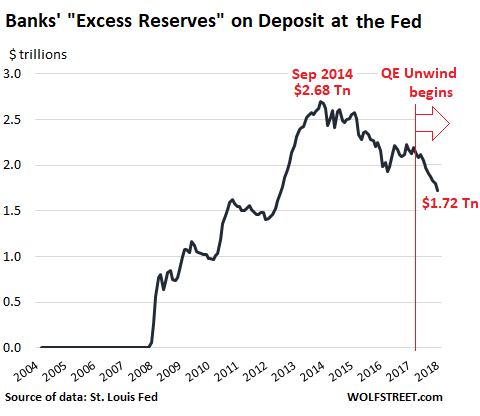

Excess reserves have been shrinking since September 2014, when they peaked at $2.74 trillion. As of October 25, 2018, they dropped to $1.72 trillion, down $1 trillion over the span of four years. But they’re far from having “normalized,” which would be zero, as before QE started:

“Banks are in a decent position right now, but over time this will begin to weigh,” Jonathan Cohn, the head of interest-rate trading strategy at Credit Suisse, told Bloomberg, with reference to that $1.72 trillion of still nearly free money that banks got from their deposit customers and have in turn placed on deposit at the Fed earning currently 2.2% risk free. These “excess reserves” provide $38 billion a year in pure profit for banks, handed to them by the Fed. Thank you for the free gift. And now the crybabies don’t want to give that up.

Bloomberg cites another Wall Street crybaby:

Michael Cloherty, the head of U.S. interest rate strategy at RBC Capital Markets, is worried. He says the biggest risk is the Fed turns a blind eye to the pressures on bank reserves and triggers huge swings in short-term rates with its balance-sheet runoff.

There haven’t been any “huge swings in short-term rates,” but they have increased steadily to the highest levels since before the era of interest rate repression as they begin to “normalize.” Normalcy, after a decade of being coddled, is a painful thing for these crybabies.

“At some point, all of the reserves outstanding will be locked up by all the people who need it” to meet all the regulatory mandates, which may lead to a “scramble” for short-term cash, he said. “If the Fed keeps shrinking its balance sheet until it sees signs of stress, the question will be, ‘How ugly is that stress?’ I think it will be quite ugly.”

This “‘scramble’ for short-term cash” is of course the market force that pushes banks to offer higher interest rates on their deposits to attract more deposits, a sign that the Fed’s interest-rate-repression decade has come to an end.

And yes, it might get “quite ugly” for asset holders because asset prices are heading south, after a decade of Fed-engineered “wealth effect.” That’s the fear, and that’s why the crybabies on Wall Street are making such a racket.