Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Forced selling by loan funds in the once red-hot $1.3-trillion “leveraged loan” market.

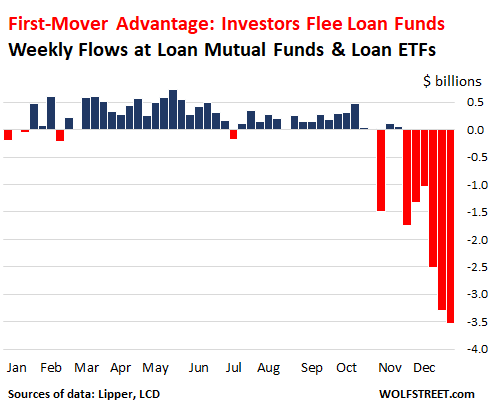

Part of the $1.3 trillion in “leveraged loans” — loans issued by junk-rated overleveraged companies — end up in loan mutual funds and loan ETFs. These funds saw another record outflow in the week ended December 26: $3.53 billion, according to Lipper. It was the sixth outflow in a row, another record. Over the past nine weeks, $14.8 billion had been yanked out, another record. These outflows are, as LCD, a unit of S&P Global Market Intelligence, put it, “punctuating a staggering turnaround for the asset class” that until October was red-hot:

Despite $10 billion of net inflows during 2018 through early October, the record outflows at the end of the year caused a net outflow for the entire year of $3.1 billion. What a sudden turnaround!

The net outflow of $3.53 billion during the final week of the year consisted of $2.9 billion that was yanked out of loan mutual funds and $626 million that was yanked out of loan ETFs.

In addition, during the week, prices of these loans dropped. Lipper reported that the balances at loan funds fell by another $746 million “due to market value.” The total amount in leveraged loans that loan funds now hold has dropped to $91 billion. So the $746 million drop due to “market value” during the week amounted to a price drop of 0.8%.

The rest of the $1.3 trillion in leveraged loans are held by institutional investors, hedge funds, pension funds, etc., or have been packaged into collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) that were sold to institutional investors globally.

It can take a long time to sell a leveraged loan. Each is a unique contract, and finding a buyer and agreeing on a price and completing the sale takes time. So loan funds hold considerable amounts of cash so that they can meet redemptions. But now, loan funds faced with this onslaught of redemptions have to dump loans in order to stay ahead of the redemptions and maintain a cash cushion. This forced selling by loan funds has caused prices to drop – which is further motivating investors to yank even more out of those loan funds.

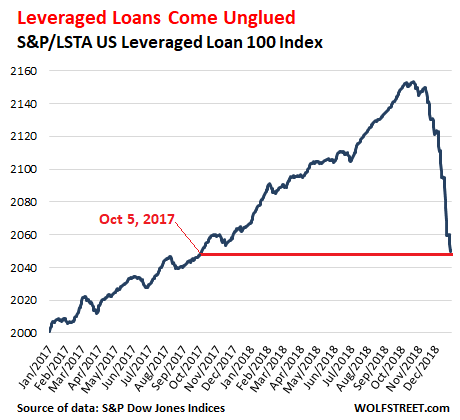

Since October 22, the S&P/LSTA US Leveraged Loan 100 Index, which tracks the prices of the largest leveraged loans, has dropped 4.8%. This price decline put the index back where it had been on October 5, 2017. But note, while there have been some defaults recently, the big wave of defaults that many expect in an environment where credit is tightening for risky corporate borrowers, hasn’t even started yet. These are still the good times:

Leveraged loans carry a floating interest rate, usually pegged to Libor. Libor has been rising in parallel with one-month and three-month US Treasury yields. And the interest that these loans pay has been rising too. Bonds that pay a fixed coupon rate lose value in a rising interest rate environment. But unlike bonds, leveraged loan generally protect investors from a price decline due to rising interest rates – which is why they were such a hot asset class over the past three years, with investors swarming all over them, and with companies issuing them in record amounts.

The risk of these floating rates is that struggling companies, faced with higher interest payments on existing loans, will be pushed into default sooner. That hasn’t happened yet in a large wave, but it’s on the horizon for the next few years.

The Fed has been warning about the risks of leveraged loans since 2014. Most recently, on October 24 – about the time the leveraged-loan sell-off started – and on December 2, in its first-ever Financial Stability Report. Perhaps investors have finally taken note.

Investors are now fleeing from open-end loan mutual funds because they know what the risks are: There is little liquidity in the leveraged-loan market even in good times, but investors can sell the mutual fund instantly. When these investors start yanking their money out of these funds in large numbers, they can create a run-on-the-fund. If the fund doesn’t have enough cash on hand to meet the redemptions and isn’t able to sell the loans fast enough into the illiquid market, the fund is then forced to sell loans for cents on the dollar to some distressed-credit hedge fund or PE firm waiting for this opportunity. And the net asset value of the mutual fund gets crushed.

Investors that grab the “first-mover advantage” in an illiquid market and are among the first out the door before they get caught in a run-on-the-fund come out unscathed. The late movers, or non-movers, in the worst-case scenario, can get caught up in the collapse of the fund. This “liquidity mismatch” makes open-end loan mutual funds riskier than the actual leveraged loans – and they’re risky enough — and investors are not getting paid for taking this risk.