Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, http://www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Who stepped up to the plate?

It’s a good thing Russia never held as many US Treasury securities as China and Japan. The scenario would have been different.

The “grand total” of US Treasury bonds, notes, and bills held by official foreign investors (central banks, governments, etc.) and non-official foreign investors rose by $44.6 billion to $6.17 trillion at the end of May, according to the Treasury Department’s TIC data released Tuesday afternoon. This is in the middle of the range of the past 12 months.

But Russia stands out by its sudden absence.

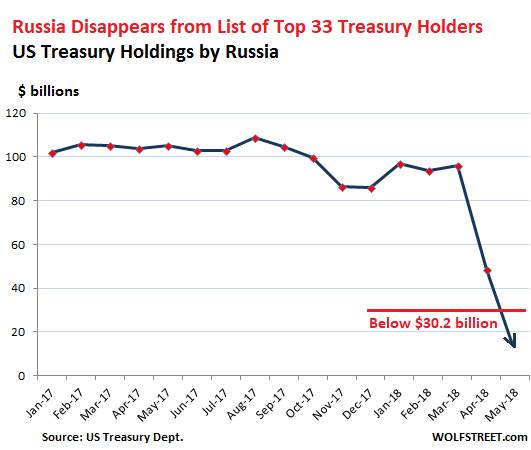

Russia was never a large holder of US Treasuries, compared to China and Japan. In March it was in 16th place with $96.1 billion in Treasury holdings. In April, it liquidated $47.4 billion of its holdings, and ended the month with $48.7 billion. That was down 69% from May 2013 ($153 billion). It knocked Russia into 22nd place behind the UAE and Thailand.

And it May, Russia liquidated more of its holdings and disappeared entirely from the TIC’s list of the 33 largest foreign holders of Treasuries. The smallest one on the list was Chile, with $30.2 billion. Russia’s holdings must have fallen below that amount, and I can imagine to zero:

If there was a message in Russia’s liquidation of US Treasuries, it was a pitch in the water: The 10-year Treasury sell-off that had started last September peaked with the 10-year yield at 3.11% on May 17. Since then, the 10-year Treasury has rallied under heavy demand, and the yield has fallen – hence the handwringing about the inverted yield curve.

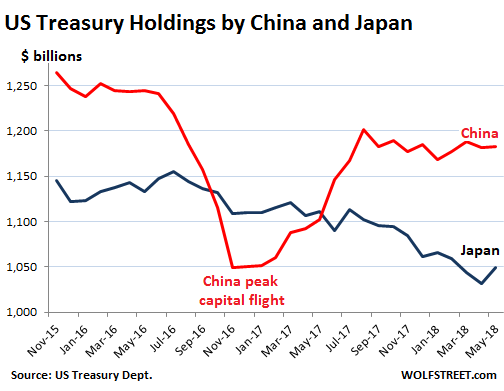

The largest holder of US Treasuries is China, a position it had lost briefly during its era of peak capital-flight from October 2016 through March 2017. Its holdings in May ticked up by $1.2 billion to $1.183 trillion. Its holdings have remained within the same range since August 2017, despite escalating threats of a “trade war.”

Japan had been systematically reducing its Treasury holdings. In April its holdings had dropped to $1.031 trillion, the lowest since October 2011. But in May, it increased its holdings by $17.6 billion to $1.049 trillion:

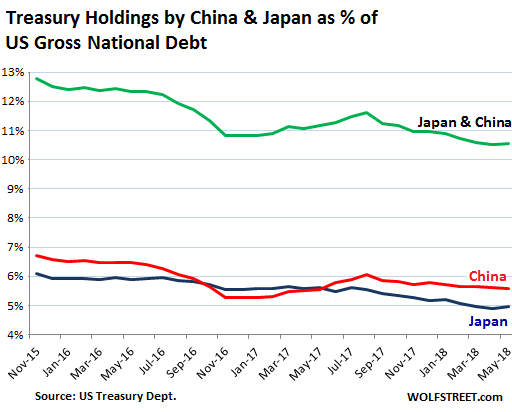

While China and Japan play an outsized role as creditor to the US, that role has been diminishing in terms of the US gross national debt for two reasons: US debt has soared; and the holdings of China and Japan have fallen over the past two years. And their combined holdings fell from nearly 13% at the end of 2015 to 10.6% in May 2018 (green line):

The largest holders of US Treasuries, after China and Japan. Note the tax havens on the list:

- Ireland: $301 billion

- Brazil: $299 billion

- UK (“City of London!”): $265 billion

- Switzerland: $243 billion

- Luxembourg: $209 billion

- Hong Kong: $192 billion

- Cayman Islands: $186 billion… down from $250 billion in April 2017!

- Taiwan: $165 billion

- Saudi Arabia: $162 billion

- Belgium: $151 billion

- India $149 billion

- Singapore $119 billion

Germany, the fourth largest economy in the world and running a huge trade surplus with the US, held only $78 billion in Treasuries in May.

Who are the remaining creditors of the US?

By the end of May – to stay within the time frame of the TIC data – the US gross national debt had reached $21.15 trillion, up about $1.2 trillion from a year earlier! And this is who held all this paper:

- $6.17 trillion (29.2%): foreign entities (see above).

- $5.72 trillion (27.1%): US government entities such as pension funds – “debt held internally.”

- $2.39 trillion (11.3%): the Fed as a result of QE

- $6.86 trillion (32.2%): Americans as institutional and individual investors, directly and indirectly, through bond funds, pension funds, and other ways.

The two-year Treasury yield, at 2.62% now exceeds the S&P 500 dividend yield of 1.8%. Neither can keep up with rising consumer price inflation as measured by CPI (2.9%). But for dividend investors seeking to limit their downside, short-term, liquid, risk-free assets such as Treasury notes with two-year maturities are suddenly a valid option. This makes Treasuries desirable, in an era where 2-year government bond yields are still negative, as in some Eurozone countries and Japan.