Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

The “up to” begins to matter for the first time.

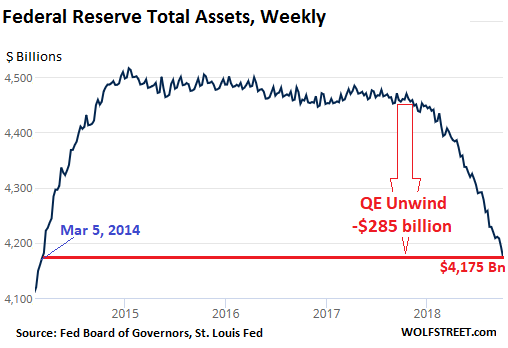

The Fed released its weekly balance sheet Thursday afternoon. Over the four-week period from September 6 through October 3, total assets on the Fed’s balance sheet dropped by $34 billion. This brought the decline since October 2017, when the QE unwind began, to $285 billion. At $4,175 billion, total assets are now at the lowest level since March 5, 2014:

During QE, the Fed bought Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). During the “balance sheet normalization,” the Fed is shedding those securities. But the balance sheet also reflects the Fed’s other activities, and so the amount of its total assets is higher than the combined amount of Treasury securities and MBS it holds, and the changes in total assets also reflect its other activities.

The QE unwind was still in ramp-up mode in September, according to the Fed’s plan. For September, the Fed was scheduled to shed “up to” $24 billion in Treasuries and “up to” $16 billion in MBS.

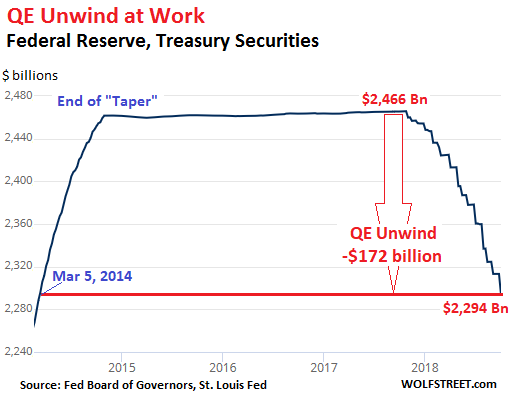

From September 6 through October 3, the Fed’s holdings of Treasury Securities fell by $19 billion to $2,294 billion, the lowest since March 5, 2014. Since the beginning of the QE-Unwind, the Fed has shed $172 billion in Treasuries:

The “up to” begins to matter

Though the plan calls for shedding “up to” $24 billion in Treasury securities in September, the Fed shed only $19 billion. Here’s what happened – and why this will happen more often going forward:

When the Fed sheds Treasury securities, it doesn’t sell them outright but allows them to “roll off” when they mature; Treasuries mature mid-month or at the end of the month. Hence, the step-pattern of the QE unwind in the chart above.

On September 15, no Treasury securities matured. On September 30, two security issues in the Fed’s holdings matured, totaling $19 billion. Those were allowed to “roll off” entirely without replacement. In other words, the Treasury Department redeemed them and paid the Fed $19 billion for them. The Fed then destroyed this money – in a reverse process of QE when it created this money with which to buy securities.

But since only $19 billion in Treasury securities matured, only $19 billion could roll off, and the “up to” $24 billion cap could not be reached.

This will happen again. For example, in October, $22.9 billion in Treasury securities will mature. In October the “up to” cap increases to the final cruising speed of $30 billion a month, but only $22.9 billion can roll off.

In November, however, $50 billion in Treasury securities will mature. The Fed will let $30 billion roll off, maxing out the “up to” cap of $30 billion, and will replace the remaining $20 billion.

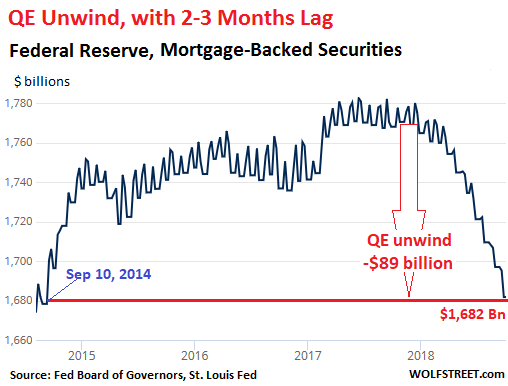

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

The Fed is also shedding the MBS on its balance sheet. The Fed acquired residential MBS that were issued and guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. Residential MBS differ from regular bonds; holders receive principal payments as the underlying mortgages are paid down or are paid off. At maturity, the remaining principal is paid off. To keep the balance of these ever-shrinking MBS from declining after QE ended, the New York Fed’s Open Market Operations (OMO) kept buying MBS.

The Fed books the trades at settlement, which occurs two to three months after the trade. Due to this lag of two to three months, the Fed’s balance of MBS at the end of September reflects trades from around June, give or take a few weeks. In September, the “up to” cap for shedding MBS was $16 billion. But at the time of the trades, through June, the cap was $12 billion. In July, it increased to $16 billion. So we would expect the roll-off that was booked in September to be somewhere between the June cap of $12 billion and the July cap of $16 billion.

And this is what we got. Over the period from September 6 through October 3, the balance of MBS fell by $14.2 billion, to $1,682 billion, the lowest since September 10, 2014. In total, $89 billion in MBS have been shed since the beginning of the QE unwind:

Based on various tidbits in speeches and discussions by Fed governors, it seems that a consensus is building that the Fed wants to get rid of all its MBS and only hold Treasury Securities. The Fed’s strategy of buying MBS under what Wall Street had wishful-thinkingly called “QE infinity” was designed to lower long-term interest rates, particularly mortgage rates. If the Fed decides to shed all its MBS and stay out of this market, it would further reduce the official support for – or rather, official manipulation of – the mortgage market, and by extension, the housing market.