Rising income inequality may be a reflection of the changing nature of work.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s story The Rich Boy included this famous line: “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” According to a recent paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER),Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century (abstract only), the “working rich” are different from you and me, and from the Oligarchs above them who pay little in U.S. income taxes due to offshore tax havens and philanthro-capitalist tax avoidance scams.

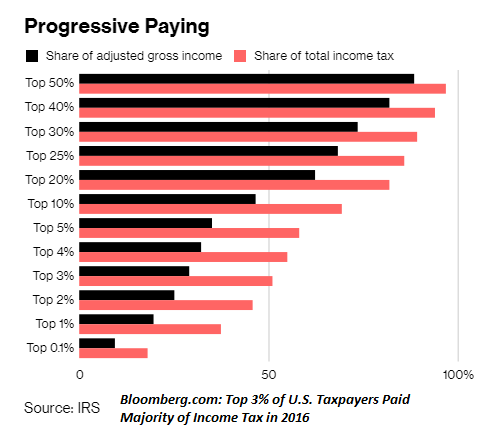

Before we start complaining about the rich not paying their fair share, let’s note that the top 3% of taxpayers–mostly “working rich”– pay more than 50% of all income taxes. The latest available IRS data is from the 2016 tax year, as reported by Bloomberg: Top 3% of U.S. Taxpayers Paid Majority of Income Tax in 2016.

The top 1% paid 37% of all income tax collected,the top 5% paid almost 60% and the top 10% paid about 70%. What’s striking is the progressive nature of taxes compared to the income of each bracket: the top 1% earned about 20% of total income but paid 37% of the income tax, the top 5% earned 35% and paid almost 60% of the income tax and the top 10% earned 46% of the income and paid 70% of the tax.

So what distinguishes the “working rich” from the Oligarch rich? The Oligarch rich collect passive, rentier income from the ownership of assets: stocks, bonds, real estate, etc. The “working rich” are owners of companies, and most of their income comes from human capital, meaning their knowledge, expertise and experience. According to the NBER authors’ research, when these “working rich” owners retire or die, business income tanks by 75%.

In contrast, the passive income from financial/physical assets continues on unchanged even if the owner retires or dies.

The “working rich” have a few tax advantages in terms of their effective tax rate, but the bottom line is they pay most of the income taxes collected by the U.S. Treasury. The “working rich” are not tax cheats like the super-wealthy revealed by the Panama Papers; they’re the ones doing the heavy lifting of paying most of the $1.7 trillion in income taxes (which doesn’t include the payroll taxes of Social Security and Medicare, with employees and employers each paying 7.65% of wages/salaries).

While a high-earner employee’s tax rate is 35% above $200,000 (and 6.2% up to $132,000 for Social Security taxes and 1.45% Medicare taxes on all earned income), business owners can shift much of their income from earnings (wages/salaries) to profits or long-term capital gains, which are taxed at lower rates.

This is the key difference between employees and the “working rich”: the working rich, as business owners, can elect to pay themselves a salary but distribute most of their income as profits or long-term capital gains, which are taxed at 15% up to $425,800 and 20% on everything above that level.

Despite this advantage, the top 1% paid an effective tax rate of 26.9% compared to 15.6% for the top 50% of taxpayers while the top 5% paid 23.5%.

The other key finding of the NBER paper is that the “working rich” kept most of the gains earned by their enterprises: rather than distributing much of these gains to employees, the business owners increased their share of net profits, a trend which has fueled the income inequality so many of us have been scrutinizing.

Why is this occurring? I have a theory. I doubt this theory lends itself easily to quantification, so it may be difficult to support statistically, but here goes: business owners are keeping more of the net gains because the commoditization of labor has reduced the incentives to retain the most experienced employees.

In terms of human capital, the gains in productivity accrue to those with long experience in difficult, high-value tasks. The most experienced employees make the most money for the firm because they can solve problems faster and more effectively than employees with less experience.

But once labor has been commoditized, i.e. sliced into discrete tasks, long experience no longer pays dividends. In a commoditized labor force, paying higher wages to retain senior workers simply doesn’t make business sense. The most profitable way to manage employees is hire the least-experienced workers, get them up to speed and then keep their wages more or less the same. If they leave for another job, the tasks they were performing can be learned by new employees relatively quickly because they’ve been commoditized.

Now that even inexperienced workers are scarce in many regions, businesses are having to pay more wages and offer more flexibility to get replacement workers. But the modest rise in wages (roughly 3%, if recent estimates are accurate), are much less than the gains being accrued by successful privately owned companies.

In other words, rising income inequality may be a reflection of the changing nature of work: to streamline and automate work, labor has been commoditized wherever possible so the tasks can be performed by anyone with some training anywhere in the world.

The days in which the senior workers held the most profitable knowledge in their heads, and employers who wanted to secure strong profits paid senior workers handsomely to keep them, are largely gone. Would you pay someone $30 an hour when someone getting $20 an hour produces the same output? No wonder the “working rich” are keeping most of the gains for themselves: there’s not much incentive to reward seniority if seniority is no longer adding to the enterprise’s core human capital.