by John Rubino

A few years ago the Swiss National Bank (SNB) – which traditionally held “monetary assets” like government bonds, cash and gold to back up the Swiss franc — decided to branch out into common stocks.

This was a departure, but for a while a brilliant one. The SNB loaded up on Big Tech like Apple, Amazon and Microsoft, and rode them to massive profits, which enriched both the Swiss people and the SNB’s stockholders (in another departure, it’s a publicly traded company as well as a national central bank).

But live by the sword, die by the sword. Turning your central bank into the world’s biggest hedge fund means outsized profits in good times, but potentially serious losses if those aggressive bets go wrong.

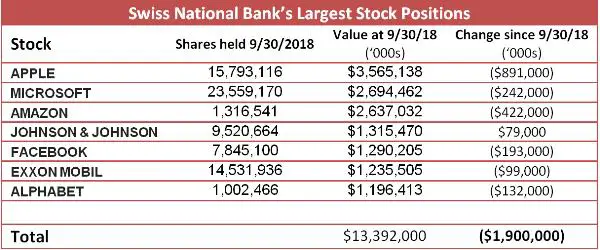

The following table shows the SNB’s seven biggest stock positions. Note that 1) they’re all US based multinationals – not a single Swiss stock – and 2) they’re all way up over the past few years but way down over the past two months. Total loss from these positions since September 30: nearly $2 billion.

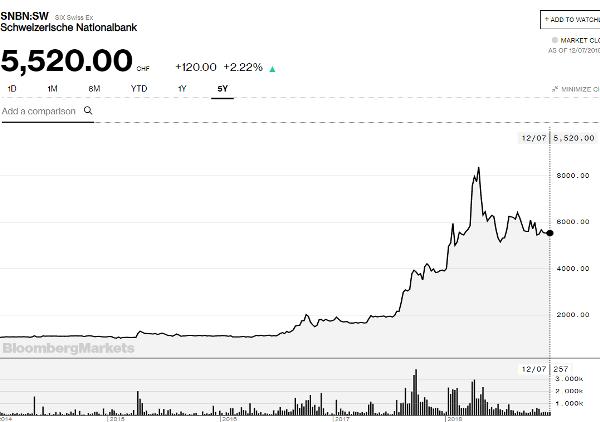

SNB’s stock price, after quadrupling during the FANG stock bubble, has given back some of that gain.

Now, why should anyone other than the Swiss and the SNB’s stockholders care whether this central bank/hedge fund wins or loses? Because of the concept of “moneyness” and what it implies for the future.

The quick version of the story is that investors generally hold a variety of assets, some of which are money and some of which are not. Money is seen as risk-free or nearly so, and makes up the part of a portfolio that is expected to hold its value. Once that risk-free core is secured, other assets that fluctuate in value are added to generate excess returns.

But – here’s where it gets interesting — at different points in the credit cycle, different things are perceived to have “moneyness.” In stressful times the range of assets perceived as risk-free shrinks down to cash, gold and major-government sovereign debt. In more optimistic times – like the later stages of a credit bubble – other things come to be perceived as having moneyness because they’ve been going up for so long that it’s hard to conceive of them behaving any other way.

This sense that Amazon and its peers can never fall, and if they do that’s just an opportunity to buy the dip, had become widespread lately, to the point that most classes of investors had bought in. Pension funds, desperate to meet their unrealistic return targets, added equity and emerging market exposure. Hedge funds whose old models stopped working in the Everything Bubble were reduced to trend following, which meant loading up on FANG stocks because they were going up. Even retirees who couldn’t live on sub-1% bank CD rates moved into growth stocks, junk bonds and emerging market debt. All had the sense that these previously-risky asset classes had, by virtue of their awesome price charts, achieved moneyness and could therefore be trusted.

But now we’ve entered the downward sloping stage of the credit cycle, and the pool of assets with moneyness is shrinking. Here’s how Credit Bulletin’s Doug Noland explains the impact:

Throughout this Bubble period, I have referred to the “Moneyness of Risk Assets.” A “run” on perceived money-like Credit instruments sparked the collapse of the mortgage finance Bubble. Runs unfold when holders of perceived safe and liquid instruments suddenly recognize risk is much greater than previously appreciated. Past crises have typically originated in the money markets. But never have central bank and government policies so fostered the perception of safety and liquidity (“moneyness”) for risk assets – equities and corporate Credit, in particular. I would argue the proliferation and massive growth of index fund products poses a major risk to financial stability. And when it comes to policy-induced distortions, already extraordinary risks to financial stability are only compounded by the proliferation and growth of derivative trading strategies, both retail and institutional.

In other words, pretty much everything the financial world is doing these days relies on a false sense of security fostered by “innovations” (ZIRP, QE, ETFs) that hide the true risks of financial assets. And people are starting to figure this out.

The ultimate end game is the realization by investors that most major asset classes – including today’s fiat currencies — lack moneyness. The resulting stampede out of the dollar, euro and yen and into real assets will be one for the history books.