Is that really what you want to spend your time doing, paying higher taxes?

“No matter how much money I make, they will always print more. I can’t print anymore time.”

The source of this quote is correspondent T.D., who shared the story of an acquaintance of his who was offered a high-paying and very demanding corporate position that would have left him nominally wealthier in terms of money but much poorer in terms of time and energy remaining after trading away the bulk of his time and energy for the higher pay.

The acquaintance turned the position down and cut the number of hours he was working, with this explanation: “No matter how much money I make, they will always print more. I can’t print anymore time.”

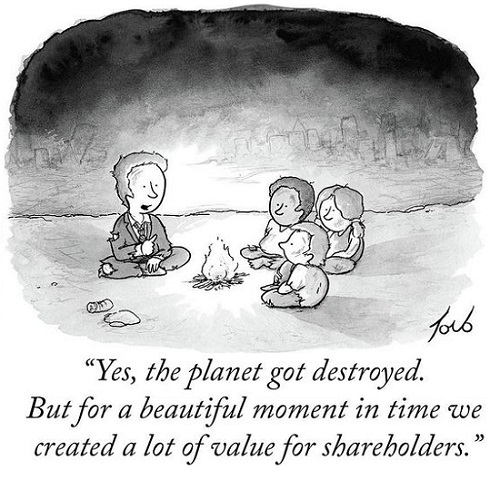

The point here is that central banks and state treasuries can always print more money, a process which reduces the purchasing power of the money they’ve issued. We can trade more hours for more money, but this extra money buys less.

No matter how much more of our time we trade for more of this created-out-of-thin-air currency, we will never be able to overcome their power to create near-infinite currency, which put another way is the power to devalue the money we trade our time for and thus devalue our time.

This is an asymmetry that should inform our decisions going forward: They Can Always Print More Money But We Can’t Print More Time.

In other words, they can devalue the money we trade our time for at will but we can’t create more time.

As catalogued in the monumental history, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the 17th Century, the history of governments’ response to crisis is depressingly repetitive: virtually without exception, every government devalues its currency in response to the soaring costs of conflict (and placating elites) and the concurrent plunge in tax revenues.

The common experience seems to be that the government-issued money loses 90% or more of its value.

In the era before central banks could create trillions of dollars with a few keystrokes, this was accomplished by recalling silver or gold coins and replacing them with coins with little intrinsic value.

In the case of the mighty Ottoman Empire of the 1600s, the empire recalled all copper coins (“small money” used for everyday transactions) and restamped it at a face value triple the old value, in effect wiping out two-thirds of its purchasing power.

Diaries of commoners in every regime not shredded by war record that the 90% devaluation of the money was just as devastating as the floods, droughts, food shortages and soaring taxes that were all part and parcel of the official response to crisis.

That money is losing purchasing power faster than we can earn more of it is a fundamental transformation. In the good old days of two generations ago, making 25% more money still added purchasing power to our incomes, even after deducting 5% for inflation (laughingly estimated at 2%) and another 10% in higher taxes paid because the extra income pushed us into a higher tax bracket.

We still netted an additional 10% of purchasing power.

But if history is any guide, then we can anticipate 20% inflation (grossly underestimated by authorities to avoid outright revolt) and 20% higher taxes (often hidden in higher “user taxes” and other flim-flam) on our additional earnings, leaving us with less purchasing power even after we traded every available hour for the additional income.

Stuck with trading our time for devaluing currency, we will be poorer in what really counts– our time and energy–and poorer in the purchasing power of our income.

This increases the temptation to gamble whatever money one has to outrace the authorities’ devaluation, and indeed, 2020’s rampant speculative bubbles generated a widespread illusion that the agile gambler could easily outrace the devaluation.

For example, take $2,000, gamble it all on the highest-volatility stocks, and turn it into $200,000. Oops, and then run the fortune to zero.

That’s the problem with relying on a hot hand in the casino to avoid trading time for money: the vast majority of punters lose in the casino, especially when the tide that’s been raising all boats ebbs away.

(Governments love gamblers who win, of course; if you live in a high-income tax state, add 9% to the federal tax rate of 32%, and be prepared to “share” 40+% of your casino winnings.)

The other approach is to reduce our need for money to a very low level so we’re not forced to trade what we cannot create more of–time–for something that’s rapidly losing value.

A second related approach is to trade our time for time-honored forms of money that have intrinsic value. While I have been on record since 2016 as saying positive things about cryptocurrencies, including my own proposal for a labor-backed cryptocurrency (A Radically Beneficial World), the historic stalwarts in the intrinsic value camp are gold and silver.

But anything with intrinsic value will do: grain, tools, nails, shelter, etc.

Having the skills to generate goods and services of intrinsic value is very much like “printing money with our time” because our skills make our time valuable, not in terms of what government currency is worth but in terms of the value others find in the goods and services we generate with our skills and time.

History informs us that governments inevitably respond to crisis by devaluing their currency and by raising taxes. In the current era, the more money commoners earn, the more taxes they pay, as taxes are progressive. The less we earn, the less taxes we pay.

Politically, this cannot change much, for as people become poorer, their ability to pay taxes diminishes. So taxes will rise on high earners, not on those earning relatively little. It may well be that every dollar of nominal gain in income will simply pay higher taxes. Is that really what you want to spend your time doing, paying higher taxes?

They Can Always Print More Money But We Can’t Print More Time. So what do we spend our precious time doing? Running the Red Queen’s Race with devaluing currencies, or lessening our exposure to the theft of our time by currency devaluation and taxes?

It’s not an asymmetry we will have to address tomorrow, but the time will come when it presses on us like gravity itself.