Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

There are now many of them. Shoring up the balance sheet is the opposite of “shareholder friendly.” It’s “creditor friendly.”

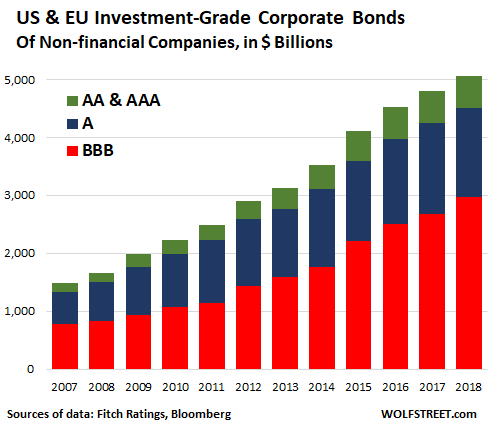

The amount of investment-grade corporate bonds outstanding by non-financial companies in the US and Europe – so excluding bonds issued by banks, insurance companies, and the like – has more than tripled (+204%) over the past ten years, from $1.66 trillion at the beginning of 2009 to $5.06 trillion by the end of 2018.

Split by rating, over the same period, according to data by Fitch:

- The amount of bonds in the lowest investment-grade category (BBB, red in the chart below) has ballooned by 262%, from $820 billion to $3.0 trillion.

- But the amount of higher- and highest-rated bonds (categories A, AA, and AAA, green and blue in the chart below) has increased “only” 147% – though that’s a huge increase too – from $842 billion to $2.1 trillion.

These are investment-grade bonds – the cream of the crop, so to speak. These amounts do not include other forms of corporate debt such as high-yield bonds (“junk” bonds), regular corporate loans, “leveraged loans,” loans by private equity firms, and other forms of debt.

But bonds in the BBB-category are teetering on the edge of “junk.” A rating of “BB+” is already in junk territory (here’s my fancy heat-sheet for the corporate credit rating scales by Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch).

In the next downturn, many bonds in the BBB-category will transition to junk, and many junk bonds but also some investment-grade bonds – if the past is any guide – will transition to default. Two-notch downgrades are not uncommon: one day you wake up, and your “BBB” investment-grade bond is a “BB+” junk bond.

So there has been a lot of handwringing about a future pileup of “fallen angels” as a historic portion of this ballooning mass of BBB-category bonds will be downgraded to junk.

A downgrade to junk makes borrowing more expensive for companies. And for companies that have to refinance debt that is coming due, this could add up. Companies are rated BBB and not A because they have a lot of debt, in relationship to their cash flow. So increasing the cost of this debt can be an issue. A downgrade to junk can also pose other problems for companies, so they generally try to avoid it.

But the strategies used to avoid a downgrade to junk can have a big bad impact on share prices, in the sense of reality coming home to roost.

To avoid a downgrade to junk, companies will try to shore up their balance sheet. This means curtailing or stopping share buybacks and slashing dividends.

This is a process GE went through. After blowing nearly $14 billion on share buybacks in the four years through 2017 to prop up its shares, GE stopped on a dime and transitioned to dismembering itself to pay down debts. The share buybacks stopped cold. Then it slashed its dividends to near-zero. And its shares have plunged.

GE now sports a credit rating of “BBB+” with negative outlook, three notches from junk, after getting hit by a round of two-notch downgrades late last year. Despite having already cut off some major limbs to reduce its debts, GE still has $97 billion in long-term debt. And GE is still trying hard to dodge further downgrades.

When a company tries to shore up its balance sheet by stopping share buybacks and slashing dividends, the result is not fun for shareholders. And even anticipating this process is not fun for shareholders. GE shares went from the $30 range in 2016 to about $9 currently, after having dipped to $7 late last year.

It’s much more fun for shareholders when the company blows billions on share buybacks to prop up its shares, and when it douses shareholders lovingly with dividends.

Ford Motor Company has $100 billion in long-term debt and is rated “BBB,” just two notches above junk. It is desperately trying to dodge those downgrades to junk. Its shares went from the $15 range in 2015 to the $9 range now. Share buybacks are off the table. Its dividend yield is an out-of-whack 6.5%. Bringing that dividend yield back into whack means one of two things: A dividend cut is coming or its shares are going to magically skyrocket.

General Motors has $73 billion in long-term debt and is rated “BBB.” Its shares are still hanging in there, in the middle of their trading range over the past five years. Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) is rated “BBB-“, one notch away from junk. Its shares have moved from the $23 range in early 2018 to the $15 range now. Kraft Heinz has $31 billion in long-term debt and is rated “BBB-” while its shares have plunged from the $90 range in 2017 to $32 range currently.

These companies have large capital requirements and must be able to refinance a lot of debt when it comes due, and they need to be able to do so without drama. They need the credit market to not worry about their balance sheet, and whether or not they will be able to refinance those debts that mature further in the future. Confidence is everything. Once that confidence begins to wobble, these over-indebted companies begin to wobble. And an investment-grade bond rating is a big factor in that market confidence.

Shoring up the balance sheet is the opposite of “shareholder friendly.” It’s “creditor friendly.” And trying to protect that BBB-rating, after years of debt-binge partying, can have a deleterious effect on share prices, even if the company succeeds in not getting downgraded to junk.

Companies buying back their own shares has “consistently been the largest source of US equity demand.” Without them, “demand for shares would fall dramatically.” Too painful to even imagine. Read… What Would Stocks Do in “a World Without Buybacks,” Goldman Asks