Rampant unaffordability and a slew of other reasons.

By Don Quijones, Spain, UK, & Mexico, editor at WOLF STREET.

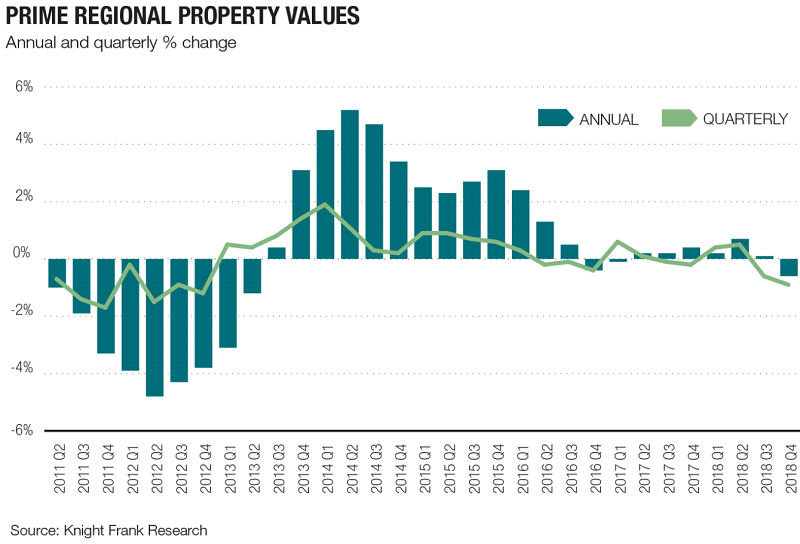

In the fourth quarter of 2018, prices in prime regional housing markets in England and Wales fell by 0.9%, according to global real estate agency Knight Frank. For the whole year, priced dropped by 0.6%, compared to 2017. The rate of annual price growth in the prime country market has averaged less than 1% since mid-2016, compared to almost 3.5% between 2014 and 2016, with peaks as high as 5% in 2014. Something isn’t working anymore:

By a different measure, across the UK as a whole, house price inflation slipped to just 0.9% in the year to November, according to a survey by LSL Property Services/Acadata that is based on every residential property transaction in England and Wales. It’s the lowest annual rate since 2012 and well below the rate of consumer price inflation. It’s also below the rate of wage inflation, which rose to 3.1% in October, its highest level in almost a decade.

There are a plethora of reasons for the current stagnation, chief among them:

- Housing unaffordability, particularly in London and other prime markets

- Dampened overseas demand

- A slew of of new taxes targeting buy-to-let landlords and overseas speculators.

- And of course, there’s Brexit.

Knight Frank lays much of the blame for stagnating or declining prices on buyer hesitancy, as acute uncertainty over Brexit and the political future of the UK deters buyers from taking the plunge. “Many, according to our sales negotiators, are choosing to sit tight and wait for clarity as the March 2019 deadline for leaving the EU nears,” the agency said.

March 29 is the deadline for the UK to reach an exit agreement with the EU.

But clarity could be a long time coming. Theresa May’s proposed Brexit deal is abhorred by Brexiters and remainers in equal measure. Offering the worst of both worlds — continued membership of the customs union and continued observance of the rules and regulations passed in Brussels, without any influence over their passage — the deal is likely to be rejected by parliament in January. That will leave two possible outcomes: a crash-out exit at the end of March, or no exit at all.

The prospect of a crash-out exit is one that many prospective and current homeowners have gradually grown to dread, especially since Bank of England governor Mark Carney’s semi-apocalyptic warning, in September, that a disorderly Brexit could wipe 35% off house prices during the immediate three-year aftermath. If the UK left the EU without a deal, he said, the Bank of England would have little choice but to hike interest rates to prevent Sterling from crashing. That, in turn, could decimate demand for housing while fueling an increase in defaults and foreclosures.

The 35% price collapse forecast by Carney sounds extreme. It would be almost double the size of any other housing crash suffered by the UK in the last 50 years, including those of the late eighties and 2008-09, when prices plunged by 20% and 19% respectively. For that alone, the Bank of England has been accused of once again serving as the shrillest of shills for Project Fear, a role it has filled with aplomb since long before the Brexit vote.

Be that as it may, even where sales are being made, they are generally taking longer to complete, particularly in the south and east of England. So far in 2018, the amount of time needed to sell a house valued above £500,000 in the South East has grown by 23% compared with 2016, Knight Frank analysis shows. In the east of England the increase is 28%. In London, the market arguably worst hit by pre-Brexit angst, it’s over 30%.

For only the second time in 23 years, house prices in London are on track to end the year with declines, according to Home Track UK’s 20-city index. It’s much worse in the most expensive parts of the city, where prices have already dropped 15% since 2014, according to James Hyman, head of the residential agency division at Cluttons. In prime central London land values are down almost 20% since hitting a peak in the third quarter of 2015. Buying and selling activity is also down.

But further price declines are welcome by potential buyers — people with decent incomes who cannot afford to buy even a modest home in London. Even as prices of land and property in the capital drop, they’re still beyond the reach of the vast majority of Londoners. The cost of the average London residence is almost 14 times the median full-time salary in the city. In select parts of the capital, homes for first-time buyers might be 20, 30 or even more than 40 times their salary.

As London-based estate agency Hamptons International reported this week, the affordability crisis in the capital is spurring Londoners to relocate to other parts of the country at the highest rate since 2007.

As for high net-worth investors — just about the only people left who can afford to buy residential property in London these days — they either have less money to spend on over-priced high-end London real estate or are splashing it elsewhere, including in other parts of the UK such as Scotland or the Midlands where median prices have respectively risen by 5.5% and 3.6% over the past year. If it weren’t for the buoyant activity in these non-prime markets, 2018 would have been an even rougher year for the UK’s property market. By Don Quijones.