Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

With QE, the Fed created money to buy securities and pump up asset prices; now it sheds securities to destroy this money.

Here’s what the Fed’s QE unwind – or the balance sheet normalization, as it calls it – is all about: it reverses over an unknown span of years a large part of what QE had done over the span of five-and-a-half years. During QE, whose stated purpose was the “wealth effect,” the Fed amassed $3.4 trillion in Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Just as the Fed spent a year tapering QE to zero, it is now spending a year ramping up the QE unwind.

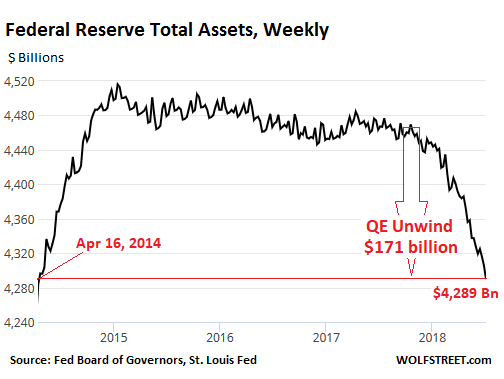

Total assets on the Fed’s balance sheet for the week ending July 4 dropped by $29.4 billion over the past four weeks. This brought the total drop since October, when the QE unwind began, to $171 billion. At $4,289 billion, total assets are now at the lowest level since April 16, 2014, during the middle of the “taper.”

The Fed’s announced plan calls for shedding up to $420 billion in securities this year and up to $600 billion a year in each of the following years until the Fed considers its balance sheet to be “normalized” — or until something major goes awry. For June, the plan calls for the Fed to shed up to $18 billion in Treasuries and up to $12 billion in MBS. So how did it go?

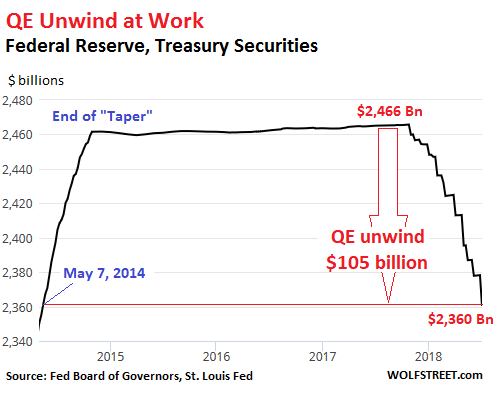

Treasury securities

The balance of Treasury securities fell by $17.5 billion in June to $2,360 billion, the lowest since May 7, 2014. Since the beginning of the QE-Unwind, $105 billion in Treasuries “rolled off.”

The step-pattern in the chart below is a result of how the Fed sheds securities. It doesn’t sell them outright but allows them to “roll off” when they mature. Treasuries only mature mid-month or at the end of the month. Hence the stair-steps.

In mid-June, no Treasuries matured, but on June 30, $30.4 billion matured. The Fed replaced about $12 billion of them with new Treasury securities directly via its arrangement with the Treasury Department that cuts out the primary dealers with which the Fed normally does business. Those $12 billion in securities, to use the jargon, were “rolled over.” But it did not replace about $18 billion of maturing Treasuries. They “rolled off.”

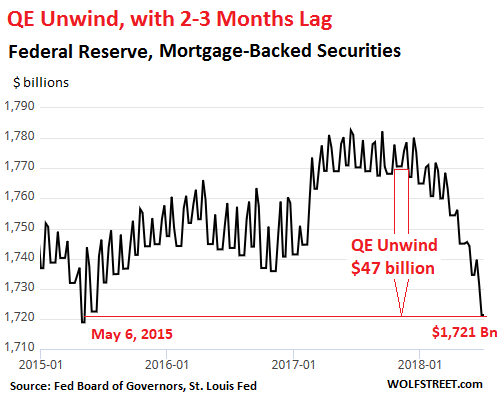

Mortgage-backed securities

The MBS on the Fed’s balance sheet were issued and guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. The credit risk lies with these entities, not with the Fed.

Residential MBS are a different breed, compared to normal bonds. Holders receive principal payments on a regular basis as the underlying mortgages are paid down or are paid off. At maturity, the remaining principal is paid off. Over the years, to keep the MBS balance from declining, the New York Fed’s Open Market Operations (OMO) kept buying MBS.

Settlement of those trades occurs two to three months later. Since the Fed books the trades at settlement, the time lag between trade and settlement causes large weekly fluctuations on the Fed’s balance sheet — the jagged line in the chart below – and caused a delay of two to three month before the declines began to show up on the balance sheet [here’s my detailed explanation].

Over the past four weeks, the MBS balance fell by $13.3 billion, to $1,721 billion, the lowest since May 6, 2015. In total, $47 billion in MBS have been shed since the beginning of the QE unwind:

What this QE unwind does is the opposite of QE: Under QE, the Fed created money out of nothing with a few clicks of its almighty mouse and bought securities with it to pump up asset prices. Now, under the QE unwind, the Fed takes the money it receives from the maturing securities and destroys it. This money just disappears to where it had come from. Just like QE added liquidity to the markets, the QE unwind is draining liquidity.

And there’s another “opposite”: QE was conducted with enormous media hoopla and Wall Street hype – they even, and ludicrously, called it “QE infinity” – to achieve the maximum “wealth effect,” namely asset price inflation; but the QE unwind occurs quietly and on autopilot, and nary a word in the media.