Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

The hail of two-notch downgrades doesn’t help.

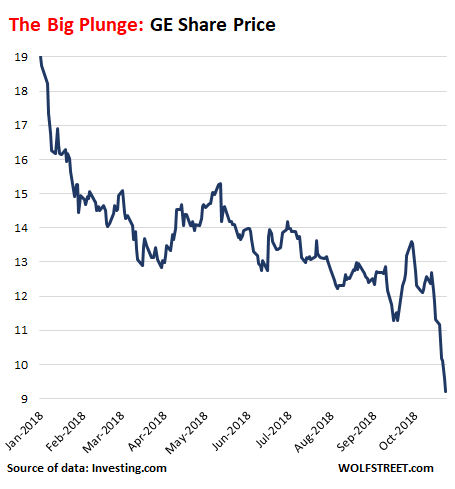

Wolf here: Shares of General Electric [GE] are down over 3% this beautiful Friday morning, trading at $9.20. If they close at this level, they would mark a new nine-year closing low. Shares are down 52% year-to-date:

The lowest close since the 1990s was $6.66 on March 5, 2009, during the Financial Crisis. I remember well: The next morning, then CEO Jeff Inmelt was on CNBC, which was owned by NBC, which was owned by GE at the time. And Inmelt was hyping GE’s shares on GE’s TV station that gave him a huge slot of time to do so, and the share price, displayed prominently onscreen, ticked up with every word he spoke.

Inmelt was also on the Board of Directors of the New York Fed, which at that time was implementing the Fed’s alphabet-soup of bailout programs for banks, industrial companies with financial divisions, money market funds, foreign central banks (dollar swap lines), and the like. This included a bailout package for GE in form of short-term loans, without which GE might have had trouble making payroll because credit had frozen up and GE had been dependent on borrowing in the corporate paper market to meet its needs, and suddenly it couldn’t. Inmelt was involved in those bailout decisions and knew what GE would get, but didn’t mention anything on CNBC.

Now Inmelt is gone from GE (resigned in 2017 “earlier than expected”), and he is gone from the New York Fed (resigned in 2011 “due to increased demands on this time”), and CNBC no longer belongs to GE, and the new CEO is trying furiously to keep the whole charade form spiraling totally out of control hoping to be able to dodge the question: “When fill GE file for bankruptcy?”

Below are some of the things that GE is doing to avoid that fate.

By Leonard Hyman and Bill Tilles for WOLF STREET:

General Electric — at one time the world’s most formidable manufacturing company and now one of the world’s most mismanaged conglomerates — suffered more financial indignities this week: Its bond ratings got hit with back-to-back two-notch downgrades: Today by Fitch Ratings, from A to BBB+ due to the “deterioration at GE Power”; and earlier this week by Moody’s, from A2 to BAA1. This follows a similar move by Standard & Poor’s earlier in October.

The rating agencies also downgraded the company’s commercial paper (CP) program, a form of short-term borrowing. Moody’s cut GE’s CP ratings from P-1 to P-2. The new, lower CP ratings effectively prevents GE from further issuance of CP. However, GE still retains access to other, higher cost bank financed short term funding vehicles. But still, not a good look.

Also this week, GE virtually eliminated its quarterly dividend, slashing it from 12 cents to a penny. A belated Halloween themed headline could read, “Boston Slasher Strikes Again.” A year earlier GE’s board voted to cut its dividend from 24 cents to 12 cents.

In our view the previous dividend reduction was better anticipated than the most recent one. Why the hurried need for a cut last week? Probably for cash conservation reasons. GE badly needs the $3.9 billion in cash saved per year to meet financial needs such as $5 billion required for an underfunded pension fund and $3 billion to shore up the capitalization of GE’s finance arm (or what remains of it).

GE also requires considerable cash to retire existing debt. One of GE’s stated financial goals is to improve ratios of debt-to-EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) to 2.5 times by 2020. In the present climate, we might refer to this as virtue signaling. Except here GE’s principal goal is to keep its respectable, investment-grade bond ratings.

The debt burden that GE’s management is presently struggling with stems from a strategy of borrowing heavily for M&A over the past decade. The biggest (and probably worst) was its purchase of French electrical equipment manufacturer Alstom in 2015 in which GE outbid arch rival Siemens. GE paid top dollar just as the market for electrical equipment began a sharp slide. This acquisition was recently written down by $22 billion reflecting the rather subdued prospects for the global power generation. Talk about a winner’s curse.

In order to raise cash and simplify its business, GE has arranged the sale of GE Transportation (locomotives, electric motors and propulsions systems for mining equipment, etc.), plans to dispose of its Baker Hughes oil services business, and intends to spin off (while retaining control) its profitable health services division.

The power division will be split into two businesses: gas turbines and everything else. This last strategic endeavor is probably the one that rankles the most insofar as it’s about two decades too late. A true house that Edison built would have pitted the fossil vs renewables organizations and let the markets sort it out.

How did GE get into the present mess and how did it manage to miss the turning point in a business it used to dominate? Despite recent disparaging comments regarding Harvard’s case studies, we believe this is something business school professors might want to examine. But it is history. For those in the power business, buyers and users of the equipment, what is the message?

First, the manufacture of gas turbines for electric power generation has become an oligopoly. Three suppliers dominate the market: Mitsubishi Hitachi (in clear lead), Siemens, and lastly GE. Oligopolists almost by definition tend to abide one another, meaning that they do not engage in anything resembling robust competition. But with an uncertain business outlook, they may be reluctant to invest more money into their businesses. One almost immediate effect is a reduction in spending on research and development which creates a sort of feedback loop which eventually weakens product positioning against new technology.

The manufacturers may argue that the business will bottom out, that a turnaround will take place. And that revenues from servicing existing equipment will provide a steady stream of business anyway. We do not disagree with these prognostications. Renewables will not provide every new kilowatt of capacity, and gas turbines will be needed anyway to back up renewables.

But we also need to be aware that longer term the competition for gas turbines will come not from renewables but from storage devices such as batteries. In terms of capital allocation, we would wager that there is far more money chasing power storage technologies than there is chasing investment in gas turbine technology.

GE, under its new management and new CEO, Lawrence Culp, may resurrect itself as a well-run manufacturing conglomerate after paying down debt obligations and shoring up its pension obligations. The aviation and health groups (even after disposition of some shares) are large and profitable. And Baker-Hughes, despite its indefinite status, might still surprise to the upside depending on global energy prices.

However, Power, despite its worldwide decline, is still GE’s largest business. New management may succeed in growing the gas turbine business (or maybe better managing its slow decline). But to us the dividend cut symbolizes GE’s fading role in a business that it literally created. By Leonard Hyman and Bill Tilles for WOLF STREET